Get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

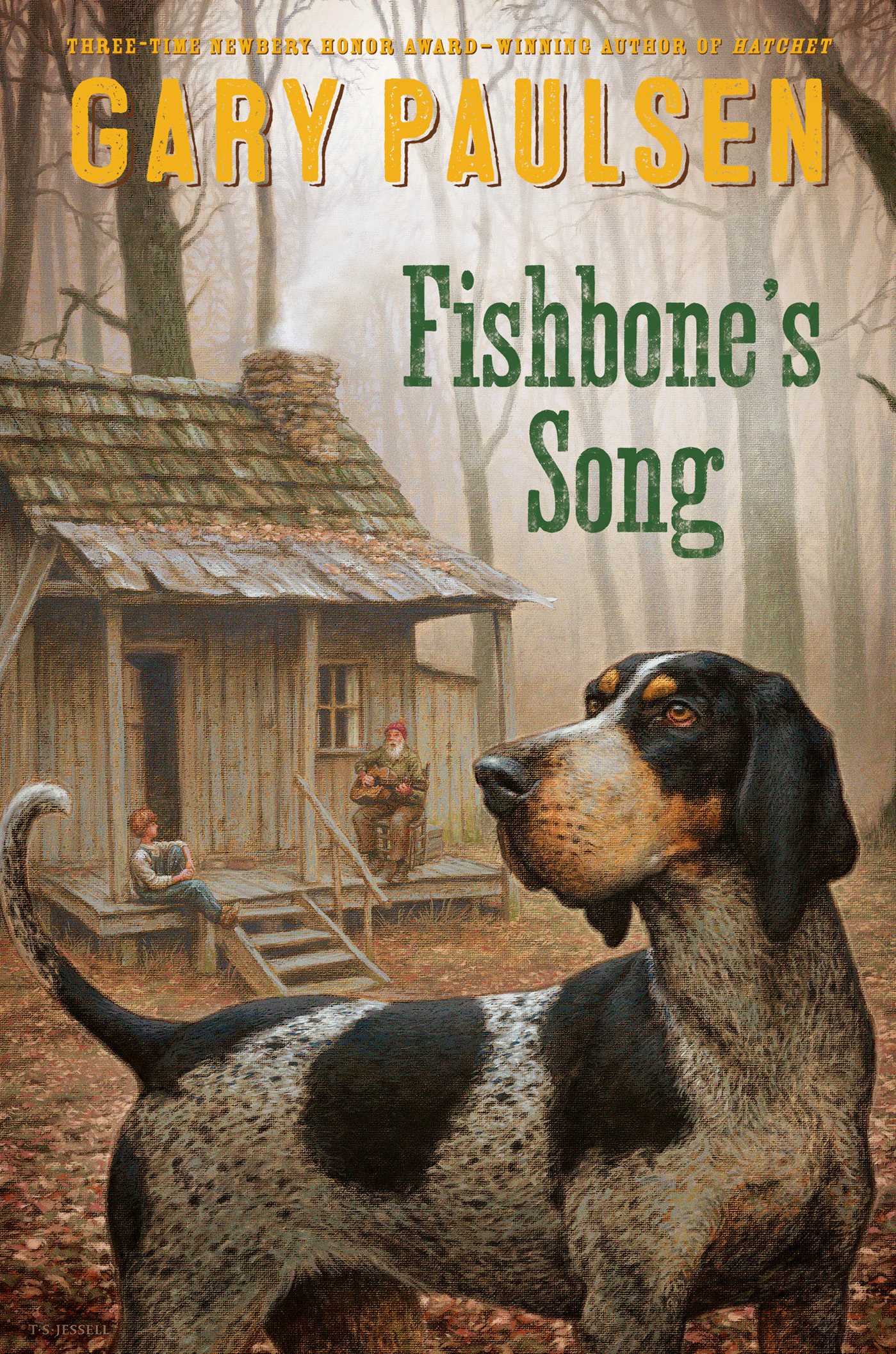

An orphan reflects on the lessons he was taught by the wise old man who raised him in this lyrical novel that reads like poetry from three-time Newbery Honor–winning author Gary Paulsen.

Deep in the woods, in a rustic cabin, lives an old man and the boy he’s raised as his own. This sage old man has taught the boy the power of nature and how to live in it, and more importantly, to respect it. In Fishbone’s Song, this boy reminisces about the magic of the man who raised him and the tales that he used to tell—all true, but different each time.

Deep in the woods, in a rustic cabin, lives an old man and the boy he’s raised as his own. This sage old man has taught the boy the power of nature and how to live in it, and more importantly, to respect it. In Fishbone’s Song, this boy reminisces about the magic of the man who raised him and the tales that he used to tell—all true, but different each time.

Excerpt

Fishbone’s Song 1 Timewhen

Could have been April when this started, this whole business about Fishbone’s song, which I ’spose could be called my song just as well. Thing is, I know where it went and sort of how long it lasted.

Or not, maybe it wasn’t really April, at least not the way time works here in the woods where we live next to Caddo Creek, just where it spills across three big rocks to make something almost like the homemade music I try to do on the old small guitar I found in the back of the caved-in ’shine shack.

I only know what the time of the day it is so that when Fishbone says:

“It’s the time when the willow bark slips enough to cut a thumb’s worth and make a high whistle for to blow. . . .” Then I know soon the creek will be swollen from the runoff out of what Fishbone calls “. . . . the long mountains,” which I’ve never seen but will someday. And then there will be the little chub fish with the rainbow on their side to net and cut in slits to smoke. And the mushrooms will come soon after the chubs run, mushrooms hiding in the grass like tiny Christmas trees until you see one and then they all seem to jump out at you, and after that to cut and dry them on a slab board in hot sun . . .

When he says that, when he says “time when,” it always comes out as one word: “timewhen.” Which he says a lot, all the time, about a lot of things. He’s old. Very old. So old he can’t really be figured in years or regular time and sometimes he’ll just say “timewhen” and not follow it up with what he was thinking about. Instead he’ll look off at a cloud even if there aren’t any clouds in the sky, and smile at some little or big thing only he knows, only he can remember. It might be something as small as a hummingbird hovering on a wild raspberry flower or as big as a war. Same smile. And he might tell you then if you ask him and he might not until later, maybe a year later, when he’s sitting on the porch smoothed with ’shine made by the man I’ve never talked to who brings the clear alcohol in the middle of a night in half-gallon canning jars. Fishbone’s old foot will tap his old work boot in a kind of tap shuffle tap, and he’ll look off into the place he was then, back then, and he’ll tell you in soft words that run together like new honey about what it was; hummingbird or war. Same voice. Same sound.

Nobody knows why they call him Fishbone or even when it might have got started as a name for him. He once said it was because he got a fishbone stuck in his throat and two doctors had to hold him in a half-broken-down wooden chair full of splinters and knots, one holding his mouth open while the second one, who was younger, dug down in his throat with a rusty pair of horseshoe tongs. They pulled out the bone, which came from a big old yellow channel catfish caught off a mudbank, and all he had to ease the pain was two swallows of clear corn moonshine . . .

All the parts of the story tight and told like they were true and they might have been, probably were, the true story. Except that maybe a week later he would tell it different and say that it was when he was fishing for crawfish and had no small hook and had to make one from the backbone of an ugly gar fish he killed in the shallows with a piece of driftwood he used for a club.

And it was not until later, on a still summer night, sitting on the porch listening to the whine of night bugs hitting the water in the dog dish where the moon had come down to sit, that you would find that both stories were true or were thought true . . .

Thoughttrue.

Like timewhen.

All the same, all the same time or place or something happening. No difference in those things because the main part was that it was his name.

Fishbone.

Stories about how I came to be with Fishbone, by him, of him, family to him—all true, all different. All told by the stove in cold times or on the porch on summer evenings while he was sipping ’shine from an old jelly jar or doing what he called “hogging around” in the garden.

First story I heard I was a baby still in birth blood in a wooden beer crate down where the creek crossed under the county firebreak trail. The trail was right on the edge of being a road that sometimes people would use to come into the dark woods, the old woods, for their own reasons, sometimes dark reasons.

Ugly, he said.

Ugly and wrinkled like a baby pink rat and squalling like a hog stuck in a fence. He found me from the noise I made just before a bear got me. Fishbone was working the creek for chubs or maybe a turtle to eat, and he yelled at the bear that was dragging the crate away, and it dropped the crate and ran off, and Fishbone took the crate and me home with him. Was the crate that was in his mind first, he said; it had iron corners bracing good clear pine wood slats that would work just near perfect in back of the stove to hold wood. When he got to it and saw me, saw what it was that had been squalling and screaming, he just took it all home, crate, baby, and all. Thought, he said, that the baby wouldn’t last long anyway and he’d bury it when it passed and still have the crate for the back of the stove. Like any other thing that came drifting down the creek that he could find to use.

I was, he said, like Moses in the Bulrushes, drifting down a river . . .

Which sounded made up until I learned to read and found the story in a big leather book. But I still don’t know what a bulrush is except it’s something to do with water and has nothing to do with bulls. Or me, for all that.

Could have been a tale like the story about his name, about the stuck bone or the small gar fish hook. Especially when you heard the other stories about how he had a second or third or fourth cousin who had a daughter who found herself with a baby she didn’t much want or know how to raise. It—I, that is—went from cousin to sister to cousin, until finally I came down to being with Fishbone who was already old, so very old, and he didn’t have anything to do for the rest of his life except live in a tumbledown cracky-shack in the woods, and so I had a home.

Third story was I was left with a note in a cardboard box on a church step. The God man who found me there knew somebody from the family that took in kids, and they knew somebody else who could take a kid, but none of them could have any more kids to care for. I wound up with a state woman who looked for blood family and that brought her, finally, to Fishbone, and since we come from some same kind of family blood, I was given to him.

To raise.

And other stories about being found where fairy families had left me under the side of a night-glowing old stump in a shallow hole. Fishbone was looped on ’shine and since he could feel and see things of mystery when he was on ’shine, he saw me there, in the glow from the stump. He took me home thinking I was witched and could see things ahead and maybe bring him good luck, like a piece of clear rock candy or a double yolk egg when you crack it in the pan. If the yolks don’t break before they fry . . .

All mixed stories and seemed to be made up except:

Except.

In back of the stove is the wooden beer crate with good pine slat sides and steel-braced corners and some old stains that might have been left by my birth blood.

And.

When they come to get me and made me go to school for a year and a little more until they knew I could never fit in, had some big words about how I could never fit in and brought me back to live with Fishbone, with my family, but in the meantime taught me to read. Right there, right then, I saw an old letter from the state said they would send a little check to Fishbone once a month to raise me in a “goodly manner.”

And.

When I came on being maybe ten or eleven or twelve years in the world, I was hunting of an evening for either a fox squirrel or a grouse because Fishbone had a feeling he wanted to eat one or the other and I came into a gulley and there it was . . .

A stump, a fairy stump where I could have been put down in a small hole as a new baby by the woods people, the night woods people, their stump, glowing blue-green in the new dark so pretty it almost had a sound, a blue-green sound I tried to make on the guitar as part of his song, Fishbone’s song. And you take that along with finding that I sometimes see things ahead—like I can know, absolutely know for certain if a squirrel is on the other side of a tree even without seeing him. Know enough to make the sound, the “chukker” sound that will bring his head around the side for the one clear shot so you don’t ruin any meat with the bullet and you kill him with the brain shot so very sudden the death smell, the gut smell, won’t taint the stew. All without seeing the squirrel first, just knowing it’s there.

So then true, all the stories about how I came to be with Fishbone were true, or could be true, thought true.

Thoughttrue.

Or maybe none of them.

But there was the wood box, and the letter from the state, and the glowing stump, and me, there I was, and Fishbone, and the woods, and the creek. So who can say which is real or not completely quite?

And Fishbone’s song, his first song, with a hum at first and then the words all coming in an up-and-down roll to match the old boot tapping and sliding on the porch boards to make time, and a soft shuffle sound like the boot was dancing and drumming at the same time.

First Song: Witching Boy

Witching boy,

in the night,

in the night.

Witching boy,

brings the light,

brings the light.

For everyone to see,

and know,

Witching boy,

brings the glow,

of life.

Shine on, shine on, Witching boy.

Could have been April when this started, this whole business about Fishbone’s song, which I ’spose could be called my song just as well. Thing is, I know where it went and sort of how long it lasted.

Or not, maybe it wasn’t really April, at least not the way time works here in the woods where we live next to Caddo Creek, just where it spills across three big rocks to make something almost like the homemade music I try to do on the old small guitar I found in the back of the caved-in ’shine shack.

I only know what the time of the day it is so that when Fishbone says:

“It’s the time when the willow bark slips enough to cut a thumb’s worth and make a high whistle for to blow. . . .” Then I know soon the creek will be swollen from the runoff out of what Fishbone calls “. . . . the long mountains,” which I’ve never seen but will someday. And then there will be the little chub fish with the rainbow on their side to net and cut in slits to smoke. And the mushrooms will come soon after the chubs run, mushrooms hiding in the grass like tiny Christmas trees until you see one and then they all seem to jump out at you, and after that to cut and dry them on a slab board in hot sun . . .

When he says that, when he says “time when,” it always comes out as one word: “timewhen.” Which he says a lot, all the time, about a lot of things. He’s old. Very old. So old he can’t really be figured in years or regular time and sometimes he’ll just say “timewhen” and not follow it up with what he was thinking about. Instead he’ll look off at a cloud even if there aren’t any clouds in the sky, and smile at some little or big thing only he knows, only he can remember. It might be something as small as a hummingbird hovering on a wild raspberry flower or as big as a war. Same smile. And he might tell you then if you ask him and he might not until later, maybe a year later, when he’s sitting on the porch smoothed with ’shine made by the man I’ve never talked to who brings the clear alcohol in the middle of a night in half-gallon canning jars. Fishbone’s old foot will tap his old work boot in a kind of tap shuffle tap, and he’ll look off into the place he was then, back then, and he’ll tell you in soft words that run together like new honey about what it was; hummingbird or war. Same voice. Same sound.

Nobody knows why they call him Fishbone or even when it might have got started as a name for him. He once said it was because he got a fishbone stuck in his throat and two doctors had to hold him in a half-broken-down wooden chair full of splinters and knots, one holding his mouth open while the second one, who was younger, dug down in his throat with a rusty pair of horseshoe tongs. They pulled out the bone, which came from a big old yellow channel catfish caught off a mudbank, and all he had to ease the pain was two swallows of clear corn moonshine . . .

All the parts of the story tight and told like they were true and they might have been, probably were, the true story. Except that maybe a week later he would tell it different and say that it was when he was fishing for crawfish and had no small hook and had to make one from the backbone of an ugly gar fish he killed in the shallows with a piece of driftwood he used for a club.

And it was not until later, on a still summer night, sitting on the porch listening to the whine of night bugs hitting the water in the dog dish where the moon had come down to sit, that you would find that both stories were true or were thought true . . .

Thoughttrue.

Like timewhen.

All the same, all the same time or place or something happening. No difference in those things because the main part was that it was his name.

Fishbone.

Stories about how I came to be with Fishbone, by him, of him, family to him—all true, all different. All told by the stove in cold times or on the porch on summer evenings while he was sipping ’shine from an old jelly jar or doing what he called “hogging around” in the garden.

First story I heard I was a baby still in birth blood in a wooden beer crate down where the creek crossed under the county firebreak trail. The trail was right on the edge of being a road that sometimes people would use to come into the dark woods, the old woods, for their own reasons, sometimes dark reasons.

Ugly, he said.

Ugly and wrinkled like a baby pink rat and squalling like a hog stuck in a fence. He found me from the noise I made just before a bear got me. Fishbone was working the creek for chubs or maybe a turtle to eat, and he yelled at the bear that was dragging the crate away, and it dropped the crate and ran off, and Fishbone took the crate and me home with him. Was the crate that was in his mind first, he said; it had iron corners bracing good clear pine wood slats that would work just near perfect in back of the stove to hold wood. When he got to it and saw me, saw what it was that had been squalling and screaming, he just took it all home, crate, baby, and all. Thought, he said, that the baby wouldn’t last long anyway and he’d bury it when it passed and still have the crate for the back of the stove. Like any other thing that came drifting down the creek that he could find to use.

I was, he said, like Moses in the Bulrushes, drifting down a river . . .

Which sounded made up until I learned to read and found the story in a big leather book. But I still don’t know what a bulrush is except it’s something to do with water and has nothing to do with bulls. Or me, for all that.

Could have been a tale like the story about his name, about the stuck bone or the small gar fish hook. Especially when you heard the other stories about how he had a second or third or fourth cousin who had a daughter who found herself with a baby she didn’t much want or know how to raise. It—I, that is—went from cousin to sister to cousin, until finally I came down to being with Fishbone who was already old, so very old, and he didn’t have anything to do for the rest of his life except live in a tumbledown cracky-shack in the woods, and so I had a home.

Third story was I was left with a note in a cardboard box on a church step. The God man who found me there knew somebody from the family that took in kids, and they knew somebody else who could take a kid, but none of them could have any more kids to care for. I wound up with a state woman who looked for blood family and that brought her, finally, to Fishbone, and since we come from some same kind of family blood, I was given to him.

To raise.

And other stories about being found where fairy families had left me under the side of a night-glowing old stump in a shallow hole. Fishbone was looped on ’shine and since he could feel and see things of mystery when he was on ’shine, he saw me there, in the glow from the stump. He took me home thinking I was witched and could see things ahead and maybe bring him good luck, like a piece of clear rock candy or a double yolk egg when you crack it in the pan. If the yolks don’t break before they fry . . .

All mixed stories and seemed to be made up except:

Except.

In back of the stove is the wooden beer crate with good pine slat sides and steel-braced corners and some old stains that might have been left by my birth blood.

And.

When they come to get me and made me go to school for a year and a little more until they knew I could never fit in, had some big words about how I could never fit in and brought me back to live with Fishbone, with my family, but in the meantime taught me to read. Right there, right then, I saw an old letter from the state said they would send a little check to Fishbone once a month to raise me in a “goodly manner.”

And.

When I came on being maybe ten or eleven or twelve years in the world, I was hunting of an evening for either a fox squirrel or a grouse because Fishbone had a feeling he wanted to eat one or the other and I came into a gulley and there it was . . .

A stump, a fairy stump where I could have been put down in a small hole as a new baby by the woods people, the night woods people, their stump, glowing blue-green in the new dark so pretty it almost had a sound, a blue-green sound I tried to make on the guitar as part of his song, Fishbone’s song. And you take that along with finding that I sometimes see things ahead—like I can know, absolutely know for certain if a squirrel is on the other side of a tree even without seeing him. Know enough to make the sound, the “chukker” sound that will bring his head around the side for the one clear shot so you don’t ruin any meat with the bullet and you kill him with the brain shot so very sudden the death smell, the gut smell, won’t taint the stew. All without seeing the squirrel first, just knowing it’s there.

So then true, all the stories about how I came to be with Fishbone were true, or could be true, thought true.

Thoughttrue.

Or maybe none of them.

But there was the wood box, and the letter from the state, and the glowing stump, and me, there I was, and Fishbone, and the woods, and the creek. So who can say which is real or not completely quite?

And Fishbone’s song, his first song, with a hum at first and then the words all coming in an up-and-down roll to match the old boot tapping and sliding on the porch boards to make time, and a soft shuffle sound like the boot was dancing and drumming at the same time.

First Song: Witching Boy

Witching boy,

in the night,

in the night.

Witching boy,

brings the light,

brings the light.

For everyone to see,

and know,

Witching boy,

brings the glow,

of life.

Shine on, shine on, Witching boy.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers (November 17, 2017)

- Length: 160 pages

- ISBN13: 9781481452267

- Ages: 10 - 99

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Fishbone's Song Hardcover 9781481452267

- Author Photo (jpg): Gary Paulsen Photo by Ruth Wright Paulsen(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit