Get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

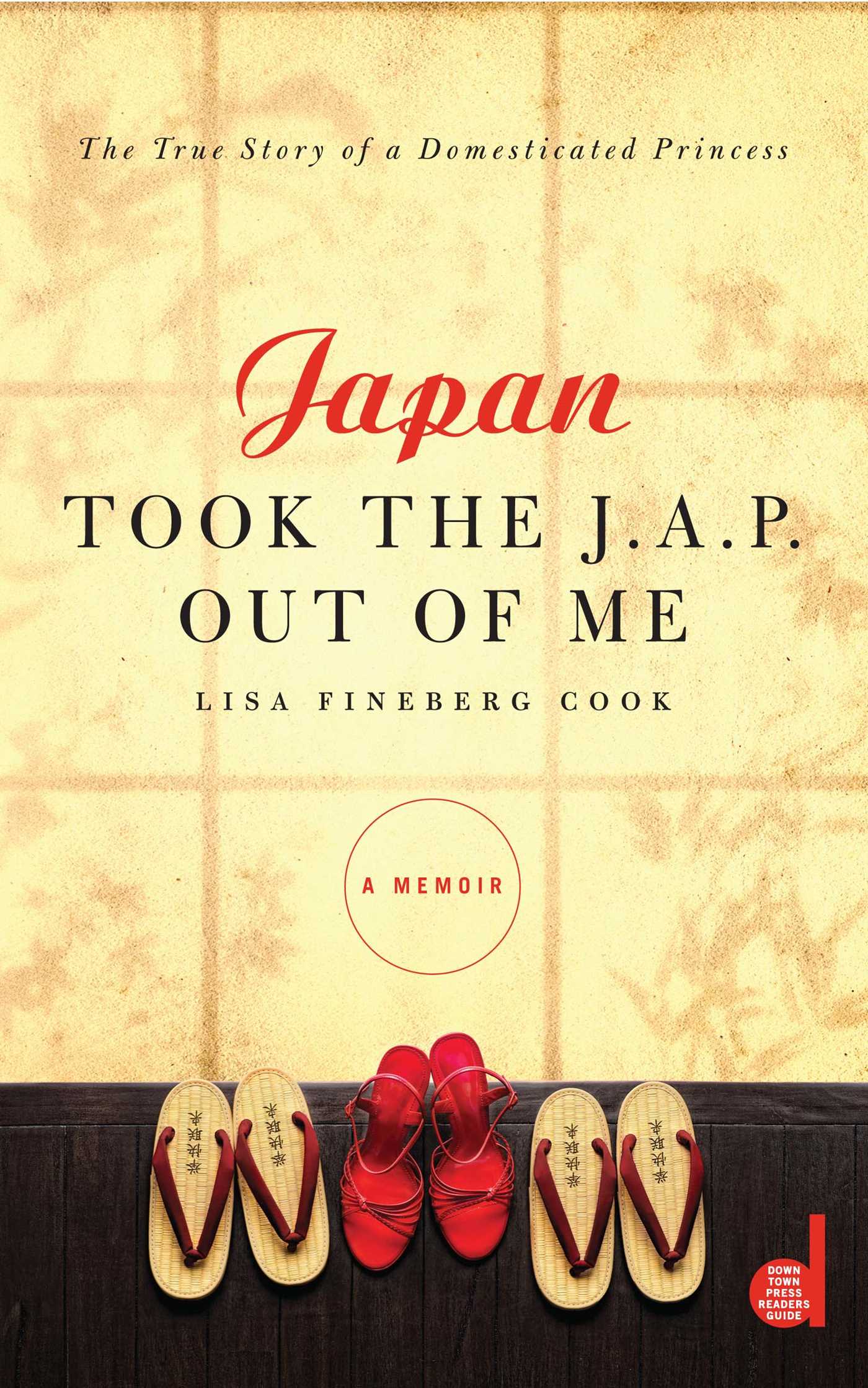

About The Book

Six days after an InStyle-worthy wedding in Los Angeles, Lisa Fineberg Cook left behind her little red Jetta, her manicurist of ten years, and her very best friend for the land of the rising sun. When her husband accepted a job teaching English in Nagoya, Japan, she imagined exotic weekend getaways, fine sushi dinners, and sake sojourns with glamorous expatriate friends. Instead, she's the only Jewish girl on public transportation, and everyone is staring. Lisa longs for regular mani/pedis, valet parking, and gimlets with her girlfriends, but for the next year, she learns to cook, clean, commute, and shop like the Japanese, all the while adjusting to another foreign concept -- marriage. Loneliness and frustration give way to new and unexpected friendships, the evolution of old ones, and a fresh understanding of what it means to feel different -- until finally a world she never thought she'd fit into begins to feel home-like, if not exactly like home.

Reading Group Guide

Join our mailing list! Get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

By clicking 'Sign me up' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to the privacy policy and terms of use, and the transfer of my personal data to the United States, where the privacy laws may be different than those in my country of residence.

Lisa Fineberg Cook, a self-described Jewish American Princess from L.A., leaps at the chance for an exciting adventure when her brand-new husband’s brand-new job takes them to Japan a week after they’re wed. Envisioning a glamorous ex-pat life in Tokyo, she’s taken aback by the reality of nowheresville Nagoya. While her husband is off teaching English to Japanese schoolchildren and adults, she—a formerly independent high school teacher—now spends her days in lonely isolation, battling the Demon washing machine and hanging cold, dripping laundry on an outdoor clothesline. Not exactly the luxe mani/pedi, high-end shopping, Sunday-brunch existence she’s used to.

Determined to learn more about her new country, Lisa begins teaching English in a girls’ high school, learning to navigate the complex subway system as well as the complex culture. As Lisa encounters gender inequality, takes a weekend trip to Hiroshima, and develops surprising relationships with her students and the Japanese women with whom she practices English conversation, her growth and emotional depth is revealed. Upon her return to the United States, Lisa realizes that being an outsider in Japan has ultimately made her more powerful inside her own culture and happier with herself.

Questions for Discussion

1. What does the Demon washing machine symbolize?

2. How does Lisa and Stacey’s relationship evolve over the course of Lisa’s memoir? Are the changes in their friendship due primarily to their geographical distance apart or other reasons?

3. Pete asks Lisa if she thinks she and Stacey have an adult relationship. Do you think that their friendship should change as they grow older? Do you agree with Pete, who suggests that one should only expect so much out of friend?

4. In terms of her attitude towards Nagoya, its culture and its people, what is the turning point for Lisa?

5. Lisa, who hadn’t lived with Pete prior to their time spent in Nagoya, attempts to hide certain quirks from him. If you’re brave enough to share with the group, what habits or idiosyncrasies might you try or have you tried to keep hidden from a significant other?

6. What do you think of gender roles as defined by the Japanese? If you were in Lisa’s position and had the forum to teach girls and women about your beliefs regarding respect and rights, would you have done the same? How would you have handled the situation differently?

7. What parts of American culture do you think might surprise or offend visitors from another country?

8. How does their time in Japan affect Lisa and Pete’s marriage? Do you think their relationship goes through any changes, and if so, are the changes particular to their circumstances? Would you consider this memoir to be a love story?

9. Lisa and Pete both experience their fair share of awkward, embarrassing moments as they adjust to their foreign world. What was your favorite funny episode in Japan Took the J.A.P Out of Me?

10. Compare and contrast Lisa at the beginning of her memoir to her at the end. How has she changed? What experiences abroad were most pivotal when it comes to her personal growth?

11. If you were to spend two years abroad, where would you like to go and what one other person would you like to go with?

A Conversation with Lisa Fineberg Cook

Japan Took the J.A.P. Out of Me covers your first year in Nagoya. Can you tell us a bit about your second year there? Did you decide not to include any stories from that time for any particular reason?

When I began writing the book, I really didn’t have a formal outline or timeline. I knew only that I wanted to start with my thoughts about the laundry. As things began to take shape, the sections evolved humorously into domestic acts, and it seemed to work better following my first year there, when things were the most awkward and significant. Plus, it seemed like every time I thought of scenarios for the book, they were ones that took place during the first year.

Did you know while you were in Nagoya that you would like to write a memoir about your experience? Were you writing at the time?

I had no idea at the time that I would ever write about this experience. I have been writing poems since I was probably nine or ten, and I always thought that if I ever got published for anything it would be poetry. Oddly, I don’t recall writing any poetry while I was living in Nagoya.

In Japan, several impediments kept you from living up to your full L.A. Retail Queen potential. Did you find that any of your shopping habits changed permanently after your time spent there?

My shopping habits absolutely changed after we left Japan, but it probably had more to do with the fact that I was pregnant with our first son when we left, and life completely shifted in terms of priorities. Nowadays, if I do shop for myself, it’s more of an accident than a planned event. With two children, when I do have time off, a day spent shopping seems like a waste of a day.

Do you keep in touch with anyone in Japan, such as your friend Maya, Ms. Sato, or your student, Eriko?

Sadly, I don’t. We moved several times: first to New York right after Japan, then to Maine, and finally back to L.A., and with all that transitioning things got lost—including my address book with the names and numbers of my Japanese contacts.

You encountered so many surprises—good and bad—in Japan. What revelation was the most shocking? Were there any additional cultural traditions or moments, or things that you discovered about yourself, that didn’t make it into the book?

I think the most shocking thing I encountered was the idea of an anti-Semitic movement in Japan. I was also shocked to see art and photography that were defaced when a woman’s genitals were involved. Any picture of a woman’s vagina was painstakingly and methodically scratched out of whatever medium it had been in. In movies, it was blacked out.

In terms of self-discovery, changes that occurred within myself have been cumulative. I learned that I am a much more serious person than I thought I was, and that certain friendships, which I had assumed would always be what they were, changed dramatically: some became stronger, some disintegrated.

Out of all the traditional Japanese food that you tried, what was your favorite dish or item?

Hands down, the two dishes I mention in the book: one being the noodles with chicken and egg at our “Flintstones” restaurant, and the other being the tenzaru at the other noodle place. I will add that one time I was taken to a traditional tempura restaurant, and I have never tasted tempura like that before or since. It was amazing.

It seems that in many ways your time spent in Japan strengthened or benefited your relationship with Peter. Do you think the experience was made harder by the fact that you were newlyweds or do you think that made things easier?

I firmly believe that the whole experience was designed to be marriage boot camp for me. I know that if we had stayed in Los Angeles, we would have a much different marriage right now. Whether that’s good or bad I don’t know, but I do know that being in a position where you have to deal with the other person all the time, that they are your only true source of companionship and guidance, and that you have to truly trust that they have your best interest at heart, requires a giant leap of faith. I can’t say whether it was harder because we were newlyweds or if it would have been easier if we weren’t, but I do know that our marriage has since weathered some pretty big storms and remains rock solid—which tells me that all the work we did in Japan meant something and helped to keep us bonded at times when we might have otherwise given up.

You were often frustrated by the inequalities between the sexes that you observed in Nagoya. Did the Japanese version of gender expectations change any of your previous feelings about the role of men and women in society and, if so, in what way?

I did and still do feel that there is a lack of equality for women in Japan that seems outdated and kind of childish. I would love to see women celebrated for their strength, wisdom, and character.

What do you miss most about Nagoya?

I miss those days on the balcony with Peter, just hanging out leisurely, deciding which adventure we wanted to take next and making it happen. I miss the decadence of being just two people in a place where we could focus on being together without distractions. Once you have children, all bets are off.

Do you and your husband have any plans to live abroad again? What about your experience in Nagoya would you like to repeat? What would you like to do differently?

We talk about it all the time. I’m sure that eventually we will live overseas again. It does become addicting. I learned in Nagoya that whatever home you are living in, fix it up quickly and make it as comfortable as you can—but do it cheaply unless you plan to be there for longer than three years. Paint goes a long way. Other than that, find the places that make you feel like a resident instead of a foreigner, such as a favorite restaurant within walking distance, a local pizza place, or something to that effect: post office, market, drug store—the things that are most universal and ritualistic.

What advice would you give to anyone considering spending a year or two in a foreign country?

Do it! Do it whenever you can, however you can: single, married, with children—whatever. It is absolutely one of the greatest things I have ever done, and when the time is right we will do it again. Don’t overplan it, overthink it, or worry too much about what will change when you’re gone. I can tell you now, it will be less than you think and more than you can imagine.

Determined to learn more about her new country, Lisa begins teaching English in a girls’ high school, learning to navigate the complex subway system as well as the complex culture. As Lisa encounters gender inequality, takes a weekend trip to Hiroshima, and develops surprising relationships with her students and the Japanese women with whom she practices English conversation, her growth and emotional depth is revealed. Upon her return to the United States, Lisa realizes that being an outsider in Japan has ultimately made her more powerful inside her own culture and happier with herself.

Questions for Discussion

1. What does the Demon washing machine symbolize?

2. How does Lisa and Stacey’s relationship evolve over the course of Lisa’s memoir? Are the changes in their friendship due primarily to their geographical distance apart or other reasons?

3. Pete asks Lisa if she thinks she and Stacey have an adult relationship. Do you think that their friendship should change as they grow older? Do you agree with Pete, who suggests that one should only expect so much out of friend?

4. In terms of her attitude towards Nagoya, its culture and its people, what is the turning point for Lisa?

5. Lisa, who hadn’t lived with Pete prior to their time spent in Nagoya, attempts to hide certain quirks from him. If you’re brave enough to share with the group, what habits or idiosyncrasies might you try or have you tried to keep hidden from a significant other?

6. What do you think of gender roles as defined by the Japanese? If you were in Lisa’s position and had the forum to teach girls and women about your beliefs regarding respect and rights, would you have done the same? How would you have handled the situation differently?

7. What parts of American culture do you think might surprise or offend visitors from another country?

8. How does their time in Japan affect Lisa and Pete’s marriage? Do you think their relationship goes through any changes, and if so, are the changes particular to their circumstances? Would you consider this memoir to be a love story?

9. Lisa and Pete both experience their fair share of awkward, embarrassing moments as they adjust to their foreign world. What was your favorite funny episode in Japan Took the J.A.P Out of Me?

10. Compare and contrast Lisa at the beginning of her memoir to her at the end. How has she changed? What experiences abroad were most pivotal when it comes to her personal growth?

11. If you were to spend two years abroad, where would you like to go and what one other person would you like to go with?

A Conversation with Lisa Fineberg Cook

Japan Took the J.A.P. Out of Me covers your first year in Nagoya. Can you tell us a bit about your second year there? Did you decide not to include any stories from that time for any particular reason?

When I began writing the book, I really didn’t have a formal outline or timeline. I knew only that I wanted to start with my thoughts about the laundry. As things began to take shape, the sections evolved humorously into domestic acts, and it seemed to work better following my first year there, when things were the most awkward and significant. Plus, it seemed like every time I thought of scenarios for the book, they were ones that took place during the first year.

Did you know while you were in Nagoya that you would like to write a memoir about your experience? Were you writing at the time?

I had no idea at the time that I would ever write about this experience. I have been writing poems since I was probably nine or ten, and I always thought that if I ever got published for anything it would be poetry. Oddly, I don’t recall writing any poetry while I was living in Nagoya.

In Japan, several impediments kept you from living up to your full L.A. Retail Queen potential. Did you find that any of your shopping habits changed permanently after your time spent there?

My shopping habits absolutely changed after we left Japan, but it probably had more to do with the fact that I was pregnant with our first son when we left, and life completely shifted in terms of priorities. Nowadays, if I do shop for myself, it’s more of an accident than a planned event. With two children, when I do have time off, a day spent shopping seems like a waste of a day.

Do you keep in touch with anyone in Japan, such as your friend Maya, Ms. Sato, or your student, Eriko?

Sadly, I don’t. We moved several times: first to New York right after Japan, then to Maine, and finally back to L.A., and with all that transitioning things got lost—including my address book with the names and numbers of my Japanese contacts.

You encountered so many surprises—good and bad—in Japan. What revelation was the most shocking? Were there any additional cultural traditions or moments, or things that you discovered about yourself, that didn’t make it into the book?

I think the most shocking thing I encountered was the idea of an anti-Semitic movement in Japan. I was also shocked to see art and photography that were defaced when a woman’s genitals were involved. Any picture of a woman’s vagina was painstakingly and methodically scratched out of whatever medium it had been in. In movies, it was blacked out.

In terms of self-discovery, changes that occurred within myself have been cumulative. I learned that I am a much more serious person than I thought I was, and that certain friendships, which I had assumed would always be what they were, changed dramatically: some became stronger, some disintegrated.

Out of all the traditional Japanese food that you tried, what was your favorite dish or item?

Hands down, the two dishes I mention in the book: one being the noodles with chicken and egg at our “Flintstones” restaurant, and the other being the tenzaru at the other noodle place. I will add that one time I was taken to a traditional tempura restaurant, and I have never tasted tempura like that before or since. It was amazing.

It seems that in many ways your time spent in Japan strengthened or benefited your relationship with Peter. Do you think the experience was made harder by the fact that you were newlyweds or do you think that made things easier?

I firmly believe that the whole experience was designed to be marriage boot camp for me. I know that if we had stayed in Los Angeles, we would have a much different marriage right now. Whether that’s good or bad I don’t know, but I do know that being in a position where you have to deal with the other person all the time, that they are your only true source of companionship and guidance, and that you have to truly trust that they have your best interest at heart, requires a giant leap of faith. I can’t say whether it was harder because we were newlyweds or if it would have been easier if we weren’t, but I do know that our marriage has since weathered some pretty big storms and remains rock solid—which tells me that all the work we did in Japan meant something and helped to keep us bonded at times when we might have otherwise given up.

You were often frustrated by the inequalities between the sexes that you observed in Nagoya. Did the Japanese version of gender expectations change any of your previous feelings about the role of men and women in society and, if so, in what way?

I did and still do feel that there is a lack of equality for women in Japan that seems outdated and kind of childish. I would love to see women celebrated for their strength, wisdom, and character.

What do you miss most about Nagoya?

I miss those days on the balcony with Peter, just hanging out leisurely, deciding which adventure we wanted to take next and making it happen. I miss the decadence of being just two people in a place where we could focus on being together without distractions. Once you have children, all bets are off.

Do you and your husband have any plans to live abroad again? What about your experience in Nagoya would you like to repeat? What would you like to do differently?

We talk about it all the time. I’m sure that eventually we will live overseas again. It does become addicting. I learned in Nagoya that whatever home you are living in, fix it up quickly and make it as comfortable as you can—but do it cheaply unless you plan to be there for longer than three years. Paint goes a long way. Other than that, find the places that make you feel like a resident instead of a foreigner, such as a favorite restaurant within walking distance, a local pizza place, or something to that effect: post office, market, drug store—the things that are most universal and ritualistic.

What advice would you give to anyone considering spending a year or two in a foreign country?

Do it! Do it whenever you can, however you can: single, married, with children—whatever. It is absolutely one of the greatest things I have ever done, and when the time is right we will do it again. Don’t overplan it, overthink it, or worry too much about what will change when you’re gone. I can tell you now, it will be less than you think and more than you can imagine.

Product Details

- Publisher: Pocket Books (October 20, 2009)

- Length: 288 pages

- ISBN13: 9781439166864

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Japan Took the J.A.P. Out of Me eBook 9781439166864

- Author Photo (jpg): Lisa Fineberg Cook Photo Credit: Manny Fineberg(0.7 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit