Get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

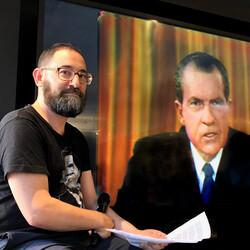

From the bestselling author of Nixonland and The Invisible Bridge comes the dramatic conclusion of how conservatism took control of American political power.

Over two decades, Rick Perlstein has published three definitive works about the emerging dominance of conservatism in modern American politics. With the saga’s final installment, he has delivered yet another stunning literary and historical achievement.

In late 1976, Ronald Reagan was dismissed as a man without a political future: defeated in his nomination bid against a sitting president of his own party, blamed for President Gerald Ford’s defeat, too old to make another run. His comeback was fueled by an extraordinary confluence: fundamentalist preachers and former segregationists reinventing themselves as militant crusaders against gay rights and feminism; business executives uniting against regulation in an era of economic decline; a cadre of secretive “New Right” organizers deploying state-of-the-art technology, bending political norms to the breaking point—and Reagan’s own unbending optimism, his ability to convey unshakable confidence in America as the world’s “shining city on a hill.”

Meanwhile, a civil war broke out in the Democratic party. When President Jimmy Carter called Americans to a new ethic of austerity, Senator Ted Kennedy reacted with horror, challenging him for reelection. Carter’s Oval Office tenure was further imperiled by the Iranian hostage crisis, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, near-catastrophe at a Pennsylvania nuclear plant, aviation accidents, serial killers on the loose, and endless gas lines.

Backed by a reenergized conservative Republican base, Reagan ran on the campaign slogan “Make America Great Again”—and prevailed. Reaganland is the story of how that happened, tracing conservatives’ cutthroat strategies to gain power and explaining why they endure four decades later.

Excerpt

RONALD REAGAN INSISTED THAT IT wasn’t his fault.

In July of 1976, Jimmy Carter emerged from the Democratic National Convention ahead in the polls against President Gerald Ford by a record thirty-three percentage points. By November, Ford had staged a monumental comeback. But it was not monumental enough. Jimmy Carter was elected president of the United States with 50.08 percent of the popular vote, and 55 percent of the electoral college.

What had stopped Ford just shy of the prize? In newspaper columns, radio commentaries, and interviews all through the rest of 1976 and into 1977, Reagan blamed factors like the Democrat-controlled Congress, for allegedly holding back matching funds owed to Ford’s campaign. And All the President’s Men, the hit Watergate movie from the spring, which Warner Bros. had rebooked into six hundred theaters two weeks before the election, for reminding voters of the incumbent’s unpopular act of pardoning Richard Nixon after Watergate. And even the United Auto Workers, for calling a strike that autumn against the Ford Motor Company—sabotaging the economy to boost Jimmy Carter, Reagan claimed.

Ronald Reagan blamed everyone and everything, that is, except the factor many commentators said was most responsible for the ticket’s defeat: Ronald Reagan.

He had challenged Ford for the nomination all the way through the convention, something unprecedented in the history of the Republican Party. Then, critics charged, he sat on his hands rather than seriously campaign for the ticket in the fall. If Ford had pulled in but 64,510 more votes in Texas and 7,232 more in Mississippi, he would have won the electoral college; or 137,984 more in Kentucky and West Virginia plus 35,473 from Missouri; or if he had won Ohio, where he came but 5,559 short, while adding either Louisiana, Alabama, or Mississippi, which Ford lost by less than two points—all of these states where Reagan had droves of passionate fans. But according to one top Republican operative, “the only effective campaign work done by Reagan was for Carter, whose ads featured Reagan’s primary attacks against Ford.” “Former Gov. Ronald Reagan has succeeded in running out the election campaign without being drawn into full, direct support for President Ford,” the New York Times had concluded—in order, the cognoscenti whispered, to preserve his own chances for 1980 should Gerald Ford lose.

Reagan howled his defense: “No defeated candidate for the nomination has ever campaigned that hard for the nominee,” but there had been “a curtain of silence around my activities.” This was not true. They were covered widely—under headlines like “Reagan Shuns Role in Ford’s Campaign.”

Now they said his political career was over. The Boston Globe’s Washington columnist joked that Richard Nixon was a more likely presidential prospect in 1980. About Reagan, the Times said, “At 65, he is considered by some as too old to make another run for the presidency.” Even right-wingers agreed—scouring the horizon, one columnist noted, “for a bright, tough young conservative whom Reagan might groom for the GOP nomination in 1980.” The Times also said that “political professionals of both major parties” believed the GOP was “closer to extinction than ever before in its 122-year history”: they controlled only twelve governorships, and, according to Ford’s pollster Robert Teeter, the loyalty of only 18 percent of American voters. Clearly, the Newspaper of Record concluded, “if the Republican Party is to rebuild it must entrust its future to younger men.”

And less conservative ones. John Rhodes, the House minority leader, was a disciple of conservative hero Barry Goldwater. His tiny caucus of 143 would face a wall of 292 Democrats when the 95th Congress convened in January. After the election, he rued that “we give the impression of not caring, the worst possible image a political party can have.” The American Conservative Union, chartered in 1964 to keep the faith after Goldwater’s presidential loss that year as the Republican nominee, felt so unwelcome in the party that they met in Chicago the weekend after the election to consider chartering a new one. Reagan himself entertained the idea until one of his biggest donors threatened to cut him off if he persisted—though Reagan did suggest that perhaps a name change for the Grand Old Party was in order. “You know, in the business I used to be in, we discovered that very often the title of a picture was very important as to whether people went to see it or not.” Even so, he had no suggestion what that should be.

THE DEMOCRATS, ON THE OTHER hand, appeared to be in clover. After Watergate, America longed for redemption. They met Jimmy Carter and fell in love.

One day that summer, the advertising man hired to make Gerald Ford’s TV commercials turned on the radio. Jimmy Carter’s mother, who’d joined the Peace Corps ten years earlier at the age of sixty-eight and whom an adoring nation called “Miz Lillian,” dialed in to a sports talk show to gab about her favorite professional wrestlers. “I was spellbound,” Malcolm MacDougall wrote. “One little phone call and 100,000 avid Boston sports fans had undoubtedly fallen in love with Jimmy Carter’s mother.”

He flipped on the TV. A Washington socialite was being interviewed by Johnny Carson. “She didn’t want to talk about her new book. She wanted to talk about her trip to Plains, Georgia. In the beginning she wasn’t a believer, she said. No, sir. She had been just as cynical as a lot of us liberals. But she’d talked with Jimmy Carter for hours. Just sat there on the porch, the two of them, talking about life and government and religion. And now she was a believer. Jimmy Carter was real, she said.… ‘He is going to save our country. He is going to make us all better people.’?”

MacDougall traveled to Boston’s Logan Airport to fly to the Republican convention. At the newsstand, “Jimmy Carter’s face was staring at me from dozens of magazines.” And from the covers of paperback books with titles like The Miracle of Jimmy Carter. He turned around: “A stack of T-shirts with peanuts on the front, and the words ‘THE GRIN WILL WIN.’ This wasn’t a clothing store.”

Even so, 70 percent of the electorate told pollsters they had no intention of voting in November at all. One of them, a rabbi, wrote a New York Times op-ed. “I was one of the millions who rejected Barry Goldwater’s foreign policy, voted for Lyndon Baines Johnson, and then got Mr. Goldwater’s foreign policy anyway. I, too, voted for law and order and got Richard M. Nixon and Spiro T. Agnew. And now I think of the man who promised Congress that he would not interfere with the judicial process, and then pardoned Mr. Nixon as almost his first official act.” So: no more voting. “If Pericles were alive today, he might be inclined to join me.”

The epidemic of political apathy spread particularly thick among the young. During the insurgent 1960s, the notion of universities as a seedbed of idealism was accepted as a political truism for all time. No longer. A university provost explained that he was seeing “a new breed of student who is thinking more about jobs, money, and the future”—just not society’s future. College business courses were oversubscribed. But politics? “Watergate taught them not to care,” a high school civics teacher rued. A college professor gave a speech to his daughter’s high school class, rhapsodizing about the excitement of the Kennedy years. “A few minutes into my talk I realized we weren’t even on the same planet.” He asked if they would protest if America began bombing Vietnam again. “Nothing. In desperation, I said: ‘For God’s sake, what would outrage you?’ After a pause, a girl in a cheerleading uniform raised her hand and said tentatively, ‘Well, I’d be pretty mad if they bombed this school.’?”

JIMMY CARTER KICKED OFF HIS general election campaign in Warm Springs, Georgia, on the front porch of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Winter White House.” Democrats traditionally opened on Labor Day in Detroit’s Cadillac Square. But Detroit was in the middle of a crime spree. Cadillac Square was only blocks from the Cobo Hall arena, where, the UPI reported, “gangs of black youth,” taking advantage of the fact that the cash-strapped city had been forced to lay off nearly a thousand cops, had recently set upon a rock concert, robbing, beating, and raping attendees.

So: Warm Springs it was.

Two of Roosevelt’s sons were by Carter’s side. A seventy-three-year-old Black man, subject of a famous Life magazine picture showing him playing accordion in his Navy uniform as Roosevelt’s funeral train trundled by, performed the New Deal anthem “Happy Days Are Here Again.” The Roosevelt connection marked Carter as an heir to the Democrats’ glorious liberal past. The Georgia setting invoked his Southern identity; if elected he would be the first president from the Deep South since Zachary Taylor in 1848. Featuring an African American spoke to his proud identity as a post-racist Southerner. Jimmy Carter would be the candidate for everyone. In his speech, he feinted left, comparing Ford to Herbert Hoover—another “decent and well-intentioned man who sincerely believed that government could not or should not with bold action attack the terrible economic and social ills of our nation.” He feinted right: “When there is a choice between government responsibility and private responsibility, we should always go with private responsibility.… When there is a choice between welfare and work, let’s go to work.” Then—and most importantly—he staked his claim as the candidate unconnected to the corrupt legacy of Richard Nixon: “I owe the special interests nothing. I owe the people everything.”

Ford opened at the White House, signing a series of bills before the cameras. What bills? It didn’t matter. “We agreed,” Mal MacDougall later explained, “there were no issues strong enough to decide the election.” Symbolism mattered: a trustworthy man was now in charge.

“Trust,” Gerald Ford said, jabbing at his opponent at his first campaign rally a week later, in the basketball arena of his alma mater, the University of Michigan, “is not cleverly shading words so that each separate audience can hear what it wants to hear, but saying plainly and simply what you mean.”

He received an enthusiastic volley of applause.

“Not having to guess what a cand—”

A sound like a gunshot rang out. The president, who had suffered two assassination attempts the previous September, flinched—then, realizing that it was a firecracker, continued on as if nothing had happened. The applause swelled and swelled until the entire crowd was up on its feet, as if in heartfelt gratitude at watching a political leader not being assassinated. The incident exemplified Ford’s campaign theme: he had returned the United States to normalcy.

Americans no longer had a political leader who was lying to their face. They were no longer losing a morally corroding war. Arab oil sheiks were no longer holding the economy hostage. And maybe, just maybe, the awful everyday traumas of the 1960s and 1970s might finally be over. “I’m feeling good about America!” Ford’s jingle bouncily intoned, in commercials that signposted his un-flashy ordinariness.

Jimmy Carter’s commercials sounded the same notes. They told the story of a man who had learned self-sufficiency and the value of hard work farming the same Georgia soil his family had since the eighteenth century, soil he sifted earnestly, wearing jeans and a plain flannel work shirt. His wife, Rosalynn, said, “Jimmy is honest, unselfish, and truly concerned about the country. I think he’ll be a great president.” That presidential candidates were decent people had been “obvious until Watergate,” a historian of campaign advertising observed. “Only in 1976 can a claim that a candidate is honest, unselfish, hard-working and concerned about the country warrant the conclusion that he will be a great president.”

THIS, HOWEVER, PRODUCED A PARADOX: the campaigns’ eagerness to prove their man the most sincere produced quantum leaps in artifice.

Carter’s packagers were ahead in this game. In 1972, Atlanta adman Gerald Rafshoon suggested that a future Carter presidential campaign could capitalize on Carter’s “Kennedy smile”; Carter, impressed, hired him. In 1974, Carter researchers learned audiences responded best to key words and phrases like “not from Washington,” “competence,” and “integrity”; those became Rafshoon’s palette. The peanut emerged early as a key symbol; it projected humility—an advantage, a strategist explained, since “humility was not our long suit.” On the trail in 1976, Carter carried his own garment bag onto the campaign plane, and posed for “candid” wire-service photos washing his socks in a hotel sink. Carter’s eight-year-old daughter was put up front for the cameras; by that summer, with what felt like half the country’s political journalists camped out in Plains, population 632, there was hardly a United States citizen who didn’t know that Amy charged ten cents a glass at her lemonade stand. (The couple’s three adult children, less photogenic, barely appeared.)

A former news producer named Barry Jagoda was Carter’s media wizard. He boasted that because he came from that world, not advertising, he was better at manipulating TV news—“the most critical battlefield in media politics.” For instance, on the day of the crucial Wisconsin primary, while the rest of the candidates remained behind for victory or concession speeches, Jagoda flew Carter to New York so that he could react to the returns live on a network news set. “This kind of media politics is seamless,” he explained. “It doesn’t mimic the news or play off the news. It is the news.” (The interview in which Jagoda said this was another novel feature of the 1976 campaign: image-makers publicly explaining how they made artifice look real.)

Marketing sincerity was the particular specialty of the advisor Carter admired most. Twenty-eight-year-old Patrick Caddell had been a mere seventeen when he first got into the business of political polling. He was an Irish-Catholic Massachusetts native whose family moved to Florida’s Panhandle—Dixie, culturally speaking. In 1968, for a math project, the high school senior besotted with baseball statistics and the late President Kennedy went door to door in a working-class Jacksonville neighborhood to poll residents about the upcoming presidential contest, and was struck by the insight that animated his career. He was shocked to hear, again and again: “Wallace or Kennedy, either one.” Ideologically, that made little sense; during the Kennedy administration, the segregationist Governor George C. Wallace and the anti-segregationist Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy had been sworn enemies. When Caddell asked people to explain, they gave answers like “They’re tough guys” and “You can believe them”; ideology seemed the last thing on their minds. While an undergraduate at Harvard University, Caddell opened a polling business out of his dorm room, and began devising innovative methods that built on this insight: tools for inquiring instead how the candidate made voters feel.

Americans’ dominant feeling, he concluded, was alienation. He devised tools to measure it—“trust indices,” “ladders of confidence”—and, from the results, language and symbols that his clients could deploy to convey to voters how they could salve that alienation. George McGovern hired Caddell as chief pollster for his presidential campaign in 1972, when Caddell was still at Harvard. McGovern lost soundly. But another Caddell client, twenty-nine-year-old Joseph Biden, won a senate seat after Caddell coached him not to criticize his incumbent opponent—that just made him another politician—but “Washington.” That made him an “anti-politician”—the kind Caddell preferred: candidates who spoke to what he termed the electorate’s “malaise,” and what he began calling in 1974 America’s “crisis of confidence.”

Candidates, in other words, like Jimmy Carter. Caddell was instrumental in Carter’s most important political breakthrough: trouncing George Wallace in the Florida Democratic primary. He first positioned Carter, Wallace-style, as alien to Washington; then Carter cemented the loyalty of Wallace fans by playing to Southerners’ ancient longing to really stick it to the Yankees. George Wallace’s longtime slogan was “Send them a message.” Carter’s was “This time, don’t send them a message. Send them a president.” “He is a generation ahead of most other technicians,” a Ford campaign memo worried on the cusp of the general election. “No one has yet devised a system for protecting a GOP incumbent from the Caddell-style alienation attack.”

FORD ADMAN MALCOLM MACDOUGALL WAS called to the White House for his first briefing for the fall campaign by a man they identified to him only as “Mr. Cheney,” whose office, MacDougall observed, had a safe as big as a man “that had a big sign across it saying ‘LOCKED.’?”

Pollster Robert Teeter described his recent innovation, a polling instrument that measured how warmly voters felt at the mention of a candidate’s name—a “feelings thermometer.” Ford’s temperature was forty-five: “Lukewarm.” Carter’s was twenty degrees higher. “We may fear that he’s another Nixon—a cold, calculating son of a bitch without a nonpolitical friend in the world. But this”—he pointed to the chart—“is reality. This is the Carter we have to deal with.”

Then he unveiled another innovation: the “perceptual map.” He laid down a transparent acetate sheet with scattered dots printed thereupon; with a dramatic flourish, he layered another on top, then another, then another. Each point represented a surveyed voter; each sheet, a different voter bloc. “Thousands of little dots began to cluster around Jimmy Carter. Blue-collar workers started clinging to the Carter circle. Intellectuals gathered around him. Catholics and Jews… Blacks and Chicanos smothered him with their dots. People who cared about busing dropped at his feet. People who were for gun control sided with him as well. Conservative women kissed his feet. Liberal women hugged his head. Environmentalists swarmed around him. The rich touched him. The poor clung to him.”

Their job, Teeter explained, was to wrench that geometry of pleasant associations from the opposing candidate to their own—by piling up proofs of their candidate’s trustworthiness, even as Carter’s side worked to turn Ford into the reanimated political corpse of Richard M. Nixon.

FBI director Clarence Kelley was revealed to have availed himself of $335 worth of home improvements from the FBI’s carpentry shop, and Ford appeared to be doing nothing about it. Said Carter, “When people throughout the country, particularly young people, see Richard Nixon cheating, lying, and leaving the highest office in disgrace, when they see the previous attorney general violating the law and admitting it, when you see the head of the FBI break a little law and stay there, it gives everybody the sense that crime must be okay. ‘If the big shots in Washington can get away with it, well, so can I.’… The director of the FBI ought to be purer than Caesar’s wife.” Bob Dole, Ford’s hatchet-man running mate, gave the campaign’s response. He asked how Carter could claim to be for closing tax loopholes and balancing the budget given his own “nice little savings” of $41,702 on his 1975 taxes via a credit for equipment purchased for his peanut warehouse. Then Dole was confronted with questions about a $5,000 campaign contribution he had taken from the lobbyist in charge of Gulf Oil’s illegal slush fund.

Peccadilloes were being elevated to blockbuster news status. After Watergate, journalists were frantic to expose corruption. Of a TV commercial intended to convey Carter’s untutored authenticity, the New York Times reported, “The body attached to the hand, which is never visible on the screen, belonged not to a newsman but to Gerald Rafshoon, the Atlanta advertising man who designs Mr. Carter’s ads.” On the president’s strategy of campaigning via Rose Garden photo opportunities, they described aides placing a fiberglass mat on the White House lawn before staging a “spontaneous” presidential stroll—then, “an hour later, the desk, chair, and mat had been moved and the television cameras repositioned so that Mr. and Mrs. Ford could be filmed striding into the garden from a different door”; the photograph was captioned, “President Ford shaking hands with his wife, Betty, in the Rose Garden… and doing it again for photographers who asked for a better angle.” This ceaseless questing after transparency seemed to freeze the electorate in a state of confusion, and by the third week of September, one-third of voters told pollsters they had no idea which candidate they would choose, with 40 percent saying they would not vote at all.

PUNDITS HOPED THE TRIVIALITY WOULD abate once and for all after September 23, when the first televised presidential debate since Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy locked horns in 1960 took place.

The first person ever to propose televised presidential debates was that most high-minded of presidential aspirants, Adlai Stevenson, disgusted by the development of electioneering via “the jingle, the spot announcement, and the animated cartoon,” and the prospect of yet one more year spent reciting the same canned speech in town after town in 1956. His advisors talked him out of the idea. He proposed it again for 1960 after his own political retirement: “Imagine discussion on the great issues of our time with the whole country watching.” It would “transform our circus-atmosphere presidential campaigning into a great debate conducted in full view of all the people.”

Federal statute, however, stood in the way: Section 315 of the 1934 Federal Communications Act mandated that broadcasters grant “equal time” for every announced presidential candidate, even if there were dozens. Kennedy and Nixon got around this in 1960 by having Congress vote a temporary suspension of Section 315. Subsequent incumbents, disinclined to grant their challengers equal TV billing, had their congressional allies block that option. Then keen legal minds devised a loophole: if an independent entity, like the League of Women Voters, staged debates, then the networks could cover them as “news events.” So it was, for the first time in sixteen years, that the American public would at last be treated to a reprise of what Theodore White, in The Making of the President 1960, had called a “simultaneous gathering of all the tribes of America to ponder their choice between two chieftains in the largest political convocation in the history of man.” The presidential election could finally become a contest of ideas.

Then two men set themselves down behind lecterns in a venerable Philadelphia theater—a TV stage set, actually: the panel of questioners sat in front of a wall that blocked the audience’s view of the stage, and the audience was ordered not to make a sound. The producer boasted of creating a “completely controlled environment.” Outside, police penned off an equally controlled area for demonstrators. The most cacophonous protested abortion. Carter had had his first run-in with the issue shortly after the convention, in a meeting with Catholic bishops in New York. The candidate pandered to them by disavowing a plank in his party’s platform opposing a constitutional amendment overturning the Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion, promising he would not stand in the way of such an amendment. But the bishops were not satisfied; they demanded he advocate for such an amendment. “No one told him,” the director of communications for the New York City archdiocese later remarked, “the bishops were talking of abortion as Auschwitz. Compromise was and is impossible for them.” The next month, Carter was banned from speaking in a Catholic church. In Scranton, Pennsylvania, Secret Service officers had to hustle him away from an anti-abortion mob. But the issue went undiscussed at the debate; both candidates’ positions were virtually identical: personally opposed; leave the question to the states.

Indeed, many of the most interesting issues went undiscussed. Questioning emphasized technical, bureaucratic concerns. The first exciting moments came when a producer broke a rule against showing reaction shots: Carter’s face turned sour after Ford called him a hypocrite; Ford glowered when Carter accused him of public relations stunts. “Lousy television,” the media guru Marshall McLuhan thought.

Until there arrived one of the most astonishing twenty-eight minutes in the history of TV.

Elizabeth Drew of the New Yorker asked the evening’s final question, about Congress’s eye-opening 1975 investigations of abuses by America’s intelligence agencies, including assassinations of foreign leaders: “What do you think about trying to write in some new protections by getting new laws to govern these agencies?” The president, in his dullest Midwestern drone, insisted that his executive reorganizations and new wiretapping rules took care of the problem. “And I’m glad that we have a good director in George Bush, we have good executive orders, and the CIA, and the DIA, and NASA—I mean the NSA—are now doing a good job under proper supervision…”

He pursed his lips. He sounded nervous. This was a dodgy, almost Nixonian answer. Things were getting interesting. Carter had spoken frankly and harshly on the campaign trail about the abuses of intelligence agencies. Now, with gathering intensity, he began lecturing: “One of the very serious things that has happened in our government in recent years, and has continued up until now, is a breakdown in the trust among our people in the—”

Silence. Even though his lips were moving.

A harsh electronic buzz.

The sonorous, authoritative voice of NBC anchorman David Brinkley: “The pool broadcasters in Philadelphia have lost the audio. It’s not a conspiracy against Governor Carter or President Ford… they will fix it as soon as possible.”

For hadn’t American know-how always fixed everything? Hadn’t it beat Hitler, delivered the world its first mass middle class, rebuilt Europe, put a man on the Moon, fought a war on poverty? It had, once upon a time. Once upon a time, the voices of such authoritative gray-haired white men reassured us, soothed us, guided us through the trauma of assassination and riot and Watergate and war, explained the inexplicable to us.

Not now.

The sound of a phone dialing. Carter gesticulating silently onscreen. David Brinkley breaking in, explaining nothing, again.

The scene shifted to backstage: “David, we don’t know what is happening, we’re as surprised as you are, uh, they were talking and suddenly they quit”; the backstage correspondent then tried convincing the 53.6 percent of American households that were tuning in that the debate had been “very lively.” He stuck microphones in the faces of campaign representatives, each dubiously claiming their men had scored knockout blows, that everything was going just smashingly (“… but I think the real winner tonight was the American people…”). An interviewer pronounced with a hint of triumph in his voice, “And now back to David Brinkley!”

Who, not realizing he was on the air, said nothing, then cast a glance offstage, mumbling, “I gather the debate is over, is that right?”

Then to the camera, conclusively: “So the debate is over! That’s it.”

But neither man moved. So the cameras kept filming… nothing.

It took the length of a TV situation comedy before the gremlin was finally fixed. It was announced that Jimmy Carter would continue answering where he left off. He said, “There has been too much government secrecy and not enough respect for the privacy of American citizens,” then grinned. The two men made closing statements. The ordeal ended. Eugene McCarthy, the former senator from Minnesota who was running a quixotic third-party bid but whose lawsuit to be included in the debate had failed, was asked what he thought about the interruption. He deadpanned, “I never noticed.” F. Clifton White, the political organizer most responsible for Barry Goldwater’s presidential nomination in 1964 and who was working unenthusiastically for Ford, was amazed at the sight of these “two men who were seeking to hold the most powerful office in the world… speechless at their podia like waxworks dummies, afraid to open their mouths and take charge,” and observed that if one or the other had done so, they would have won the election right then and there.

But the candidates had been trained by their handlers—trained within an inch of their lives—that one could only lose a televised debate, so they should not try anything, anything at all, that risked a mistake; they had been drilled not to sit down, or make any motion that might suggest weakness; indeed, it had required the intervention of a kindly stage manager just for the two men to wipe their sweaty brows during the interruption, because they would only do so when the cameras turned away. Some contest of ideas.

THE CONSERVATIVE WEEKLY HUMAN EVENTS began running ads: “CONSERVATIVES You still have a choice, you can WRITE IN REAGAN.” Reagan got letters from adoring fans asking him why they shouldn’t. He always responded by pointing to the party platform—“written by people who support me… based on the positions I took during the campaign.… If Republican victory does occur based on our platform (and it is our conservative platform) then we can continue to build from there.” He also said that if Ford should lose, it would be time to “reassess our party and lay plans to bring together the new majority of Republicans, Democrats, and Independents who are looking for a banner around which to rally.”

The name he wished to see on that banner was clearly his own. Ronald Reagan had succeeded in turning his fight against a sitting president at the Republican convention into a nail-biter—then, on the last night, delivered an apparently impromptu speech that received more acclaim than the nominee’s, leaving many delegates in rapturous tears. Four days later he returned to the job he’d done after retiring from the California governor’s office: a five-minute daily political broadcast syndicated on hundreds of radio stations. One of the commentaries he recorded that day blamed “machine politics” in states where he had lost primaries to Ford—suggesting Ford was a corrupt political boss. He was asked in a press conference on the sidewalk outside the studio where he recorded his broadcasts, on the corner of Hollywood and Vine, about the buzz to form a conservative third party. He answered, “The Republican Party, down to less than 20 percent of the voting public, has got to reassess”—hardly a ringing endorsement of Gerald Ford.

Ford phoned Reagan, asking him angrily if he even cared about beating Jimmy Carter. The New York Times said the Reagans declined an invitation to spend the night at the White House. Ford’s running mate was asked if Reagan was snubbing them. “I don’t see any problem with Governor Reagan,” Bob Dole replied—but then Reagan’s longtime press secretary Lyn Nofziger, who was working that fall for Dole’s campaign, told the press, “It’s hard for a lot of us to generate any enthusiasm.”

What Reagan’s fans were enthusiastic about, at party meetings convened to plot the general election attack, was punishing Ford loyalists from the primaries. The chairman of the California Republicans was a former Reagan protégé named Paul Haerle who had jumped ship. Conservatives wore “Hang Haerle” buttons, complete with nooses, to the state convention. Texas’s “sounded like a convention of crickets”: hundreds of “Reagan’s Raiders” blew tiny whistles to sabotage proceedings to name a Ford man state chairman. Reagan’s most loyal supporter in the Senate, Jesse Helms, endorsed the ticket—in a speech demanding that Ford’s secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, embrace the party platform Reaganites had crafted or “resign immediately.” That platform happened to include a plank, titled “Morality in Foreign Policy,” which excoriated the Nixon-Kissinger-Ford program of détente with the Soviet Union. Conservatives’ price for supporting Ford, in other words, was Kissinger avowing loyalty to a platform that called them both immoral.

Reagan was finally persuaded to deliver a televised endorsement. The speech said virtually nothing about Gerald Ford, but a great deal about Reagan’s ambitions.

It was a quintessential Reagan performance, in every way the opposite of the bland president he was affecting to support. The elaborately dressed office set recalled the image with which many Americans still primarily associated him: hosting General Electric Theater on Sunday nights in the 1950s and early 1960s. He opened with a twinkle in his eye, arguing that this election was really about the two parties’ platforms. “There have been times in the past when party platforms were noted less for what they said than for what they avoided saying,” he said. “But this year of our Bicentennial, we find the philosophies of our parties clearly stated and clearly visible for all to see.”

(“Walk toward,” the teleprompter’s stage directions read.)

“A party platform is an actual guide to the course a party will take if and when it comes to power.”

(“Lean on chair.”)

“If that is true, then the 1976 platform of the Democrat Party charts the most dangerous course for a nation since the Egyptians tried a short-cut through the Red Sea.”

(“Sit on desk.”)

He castigated the Democrats’ endorsement of the bill cosponsored by Senator Hubert Humphrey and Congressman Augustus Hawkins, the African American representative of the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, to require the federal government to produce full employment, even if it had to create government jobs to do so—“so disastrous in its consequences to the national economy, that the Democratic leadership in the Congress dares not bring it up for a vote in this election year.” Reagan claimed it cost as much as twenty-three stacks of $1,000 bills piled as high as a fifty-story building and would produce “complete and total control of the nation’s economy from Washington.”

(“Relax,” said the teleprompter. This was the sort of thing that tended to get Reagan’s Irish up.)

He implied that Jimmy Carter had Hitlerian ambitions: “The great political temptation of our age is to believe that some charismatic leader, some party, some ideology or some improvement in technology can be substituted for an economy in which millions of individual human beings make their own decisions.… It only takes one man in power with the wrong ideas to ruin an economy, and a nation.”

He flayed the Democrats’ promise of universal health insurance, said their platform’s energy plank would “economically cripple” the companies “that are the only hope we have for developing new sources and continuing to explore for oil,” the education plank extracting “more money from you but less control by you”—while the Republican platform, which was “not handed down by party leadership” but “created out of a free and frank and open debate among rank-and-file members,” understood “that your initiative and energy create jobs, our standard of living, and the underlying economic strength of the country,” and that “no nation can spend its way into prosperity; a nation can only spend its way into bankruptcy.”

Then he lit into the Democrats for proposing to cut $5 to $7 billion out of the defense budget: “There is simply no alternative to necessary spending on defense. We pay the necessary cost in terms of tax dollars now or in freedom and lives later on.” He looked into the camera: “If you’re with your children, take a look at them. They’re very much involved in this decision. If the Democrats make a mistake in how much to spend for defense, our children will pay the ultimate price.”

The next morning, the New York Times reported that, following failed negotiations between Reagan’s advisor Michael Deaver and Dick Cheney, Reagan would not be speaking for Ford in the crucial states of Mississippi, South Carolina, Florida, Tennessee, and Kentucky, and that Cheney had received “a highly qualified answer” as to whether Reagan would cut commercials for Ford.

IN ANY EVENT, REAGAN WAS yesterday’s news. Campaign reporters soon had something more entertaining to discuss.

That summer, Jimmy Carter had sat for several far-ranging interviews with a writer named Robert Scheer. He offered frank complaints about the numbness of campaign routine, and explained why he believed pardoning Vietnam draft evaders was civic duty; thoughtfully discussed why he refused to position himself simply in either the liberal or conservative camp despite media criticism that he was trying to be all things to all people; spoke candidly about his own moral failing in neglecting to speak against school desegregation until Brown v. Board of Ed, and in supporting the Vietnam War until 1971. He was blunt about America’s failings, too, citing the CIA’s abuses of power in particular; people had become inured to that sort of thing, he complained; some perhaps even “prefer lies to truth. But I don’t think it’s simplistic to say that our government hasn’t measured up to the ethical and moral standards of the people in this country.”

The subject turned to whether he’d ever discussed the possibility of assassination with his wife; Carter replied that he was not afraid to die, and that the reason was his religious faith; and whether liberal-minded Americans needed to fear the sort of judges a devout Southern Baptist president might appoint. This spurred a long, subtle theological discussion. There might never have been a document of a candidate’s thinking quite this rich in the history of American electioneering. And if it had appeared in, say, a newsmagazine, that might have been how the interview was received. Instead, it appeared in the soft-core pornography magazine Playboy—and all anyone could think about was sex.

He was explaining why he wouldn’t be “running around breaking down people’s doors to see if they were fornicating.” The answer, he said, lay within Christianity’s conception of sin and redemption. “Christ said, ‘I tell you that anyone who looks on a woman with lust has in his heart already committed adultery.’ I’ve looked on a lot of women with lust. I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times. That is something that God recognizes I will do—and I have done it—and God forgives me for it. But that doesn’t mean that I condemn someone who not only looks on a woman with lust but leaves his wife and shacks up with somebody out of wedlock.”

“Fornicating,” “adultery in my heart,” “lust,” “shacks up”—it was like he hadn’t said anything else.

An advance text was circulated to journalists right around the time of the first debate. The Associated Press headed its dispatch with a warning: “You may find the material in this story offensive to the readers of family newspapers.” Cartoonists naturally got in on the act: Carter, in a yokel’s string tie, carrying binoculars, a Peeping Tom peeking from behind a pillar. South Carolina’s Democratic senator Ernest “Fritz” Hollings said, “Let’s hope that when he becomes president he quits talking about adultery.” Georgia’s Democratic chairman told reporters, “I’ve been everywhere today and the reaction is uniformly negative.” Reverend Pat Robertson, the son of a senator, whose Johnny Carson–style Christian talk show The 700 Club reached 2.5 million viewers nationwide, said evangelicals were “making a serious reassessment of Carter.”

After the complete Playboy issue came out—there was a spread on “Sex in Cinema 1976” featuring stills of carnal activity in no fewer than twenty-two films; the usual tasteless jokes and cartoons (guy leaving an orgy: “I don’t know who to thank, but one or more of you gives great head!”); an editorial insisting heroin was not nearly so harmful as it was made out to be; a centerfold who described herself as “half liberal, half conservative” (not unlike the fellow whose interview Americans could finally read in full by flipping to page ninety-one, between a Scotch ad and an article praising Austin, Texas, as “the only wide-open dope-and-music resort available now that students were studying again”)—and Ronald Reagan pronounced himself so disgusted leafing through it that he was too embarrassed to deposit it in a public garbage can.

A SECOND FRONT IN THE Playboy controversy opened in Texas. For Carter had also said in the interview, “I don’t think I would ever take on the same frame of mind that Nixon or Johnson did, lying, cheating, and distorting the truth.” The insult to the honor of history’s first Texan president portended a potential electoral college disaster.

Team Carter counted Southern states comprising 96 of the 270 electoral votes needed to win as in the bag, and that Democratic Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the District of Columbia would bring their total to 125. Their most important swing states were Florida and Texas, both of which had begun a halting and uneven shift to the Republicans they hoped to arrest, but with Carter’s LBJ gaffe, Republicans spied an opportunity to lock in Texas for good.

The Ford campaign assigned the task of turning the molehill into a Texas-sized mountain to John Connally, the state’s larger-than-life former governor, a Lyndon Johnson protégé who had switched parties after serving as Richard Nixon’s treasury secretary. A skilled student of his state’s traditions of populist demagoguery, Democratic National Committee chairman Robert Strauss, an old college running buddy of Connally’s, said giving him the job was like handing Jascha Heifetz a Stradivarius. Connally got to work; and soon, the Texas tide began turning.

Rosalynn Carter raced down to apologize to Lady Bird Johnson. Her husband made an emergency campaign trip. Hounded by reporters, he fudged that “after the interview, there was a summary made that unfortunately equated what I had said about President Johnson and President Nixon.” ABC’s pit bull Sam Donaldson then lectured him about the difference between a “summary” and a “transcription”; Carter backtracked, lamely; Press Secretary Jody Powell kicked up a distracting shouting match with the reporters; and Carter’s numbers in Texas continued their slide. The Ford camp moved the state to its top-priority list—quickly cutting several commercials starring John Wayne.

This was a historic development. It had been a remarkable innovation when Barry Goldwater toured the Deep South for Richard Nixon in 1960—wearing “a Confederate uniform,” Lyndon Johnson darkly joked—since no Republican had ever won electoral votes there. Then, in 1964, Goldwater won Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Louisiana. When Richard Nixon attempted to repeat the accomplishment in 1968, intimating his sympathy for the region’s desire to keep the federal government from forcing racial desegregation upon it, it was dubbed the “Southern strategy.” When he swept the South along with almost all the rest of the nation in 1972, experts wondered whether the Party of Lincoln had flipped Dixie for good.

Then, however, the Democrats nominated a Southerner, and pundits began talking about the Republican Southern strategy as a thing of the past.

But now Carter was detouring to shore up his Southern flank. The Playboy interview rendered him a figure of mockery in this most pious of American regions—as when, at a rally in Nashville, someone held up a sign reading “SMILE IF YOU’RE HORNY.” He also said, during the same event, “We’ve been deeply wounded in the last eight years. We have been hit by hammer blows in the Nixon-Ford administration”—an unforced tactical error: media referees called a foul on Carter for implicitly tying Ford too closely to Watergate, an unacceptably low blow.

He was foundering in big Northern cities, too, where his “anti-politician” ways drove leaders of urban political machines to distraction. Jules Witcover of the Baltimore Sun said the old clubhouse pols treated Carter “like a naturalized Martian rather than as a fellow soldier.” He gave Democratic congressional leaders the cold shoulder, didn’t pay respects to past Democratic presidential candidates, and was even said to hold his party’s royal family, the Kennedys, in contempt—and who ever heard of a Democrat doing that? Boston’s mayor called Carter “a very strange guy, and people out there sense it too.”

Ford began gaining—until his campaign was rocked by a gaffe.

It turned on the issue of race. Richard Nixon had once been a friend to Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement, receiving 40 percent of the Black vote in 1960. Then, however, the Republican Party changed directions on the issue for good: they nominated Barry Goldwater, who voted against the 1964 Civil Rights Act. He got only 6 percent of the Black vote. In 1968, Nixon followed Goldwater’s lead, aiming his appeal at white segregationists in the South, and white Northerners opposed to busing to desegregate public schools. In 1972, nonwhites were practically the only voters who didn’t support Richard Nixon, giving him 13 percent. But for some Republicans this new reality had not yet sunk in. Mal MacDougall predicted Ford would receive “what a Republican presidential candidate can normally expect”: 30 percent of the Black vote.

Not likely now. Late in September a Rolling Stone dispatch related a conversation that took place aboard an airplane bearing pop star Sonny Bono, the squeaky-clean crooner Pat Boone, and a member of Ford’s cabinet to California after the Republican convention.

“It seems to me that the Party of Abraham Lincoln could and should be able to attract more Black people,” Boone reflected. “Why can’t this be done?”

The cabinet secretary smiled mischievously: “I’ll tell you why you can’t attract coloreds. Because the coloreds only want three things. You know what they want?”

Boone shook his head.

“It’s three things: first, a tight pussy; second, loose shoes; and third, a warm place to shit. That’s all!”

Another magazine divined that the jokester was Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz. He was an enormously consequential figure, the person most responsible for radically transforming American farming from a family-based to an industrial enterprise, but now the main thing he would be remembered for was a racist dirty joke. The press pounced—once their nervous editors figured out how to report it in a sufficiently family-friendly manner. (In San Diego, the biggest local paper offered readers a copy of the unexpurgated text only upon written request.) Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, a Republican, the Senate’s only African American, demanded Butz’s resignation. Ford dithered for several days, then, on October 3, he convened a press conference at which an ashen-faced Butz announced he was quitting, then left the room; then, Ford warmly praised him.

A boost from Ronald Reagan sure would have helped about then. Dole traveled to Reagan’s home to negotiate more campaign appearances. Reagan agreed to only one, in New Haven (where, he said, he was visiting his son for the Yale homecoming game), and refused a spot as honorary campaign chairman. In a driveway press conference, he once more praised the Republican platform; then, asked if Ford should campaign beyond the White House, mocked him. (“Wellll he’s sure got the best-televised Rose Garden in America.”) He had just published a column hymning the platform’s “Morality in Foreign Policy” plank, “unique in party platform history in its implicit recognition of past foreign policy mistakes under the party’s own leadership”—which meant Ford’s leadership.

He finally agreed to tape some commercials. The scripts he submitted kept referring to the tainted word “Republican,” which the campaign’s strategy was to avoid at all costs. After Reagan refused to rewrite them, MacDougall concluded, “It was pretty clear to me that Reagan was either coming into this thing on his terms—and with his scripts—or not coming in at all.”

THE REPUBLICANS DEBUTED A SLICK new set of commercials with the slogan “President Ford: He’s Making Us Proud Again”; and an intentionally non-slick commercial starring the amiable Black entertainer Pearl Bailey. (“I’m not reading this off any paper.… I like Gerald Ford. I don’t know who you like. But mostly he has something I like very much in every human being—simplicity, and honesty.” Then, with an authentic-sounding catch in her voice: “I don’t know, please think about it!”)

Carter spoke at the National Conference of Catholic Charities. He said that he believed the family was the “cornerstone of American life,” regretted that “our government has no family policy, and that is the same as an anti-family policy,” and promised a White House conference on the subject. This would prove an important development in years to come.

Ford signed a tax relief bill in the Oval Office. His handlers would have preferred the Rose Garden, but forecasts predicted rain.

Then it was off to prepare for the second televised debate, on foreign policy.

Ford scrimmaged with the help of another innovation of Bob Teeter’s: demographically representative audiences pressed a button to register their reactions in real time. Carter was drilled to look at the camera and smile more—and to attack the Republican from the right. He answered the first question with steely eyes, sounding like Reagan: “Our country is not strong anymore; we’re not respected anymore.… We talk about détente. The Soviet Union knows what they want in détente, and they’ve been winning. We have not known what we wanted, and we’ve been out-traded in almost every instance.”

He looked into the camera and smiled—one of forty-two grins that night, according to researchers from the State University of New York at Buffalo, compared to eight in the first: “This is one instance in which I agree with the Republican platform.”

(“That stiff, prissy man on the screen,” the former Mrs. John F. Kennedy, Jacqueline Onassis, clucked to a friend.)

Max Frankel, a distinguished New York Times editor, in a follow-up question to Ford, also suggested détente had gone too far. “Our allies in France and Italy are now flirting with Communism. We’ve recognized a permanent Communist regime in East Germany; we virtually signed, in Helsinki, an agreement that the Russians have dominance in Eastern Europe, we bailed out Soviet agriculture with our huge grain sales, we’ve given them large loans, access to our best technology. Is that what you call a two-way street of traffic in Europe?”

“Helsinki” referred to a 1975 accord in which the Soviet Union acknowledged the importance of the principle of human rights in exchange for the U.S. affirming the territorial integrity of the Eastern European states within the Soviets’ sphere of influence—which conservatives decried as a permanent surrender to Soviet control. Ford had worked very hard rehearsing an answer meant to deflect that impression. He was supposed to affirm “the independence, the sovereignty, and the autonomy of all Eastern European countries,” while asserting “we do not recognize any sphere of influence by any power in Europe.” He delivered the first part flawlessly, noting that among the Helsinki signatories was the Vatican, and that “I can’t under any circumstances believe that His Holiness would agree, by signing that agreement, that the thirty-five nations have turned over to the Warsaw Pact nations the domination of Eastern Europe.”

He muffed the second part. He said, “There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, and there never will be under a Ford administration.”

From the panelists’ table in front of the stage, the moderator called for Carter’s riposte—but Frankel broke in incredulously:

“I’m sorry, could I just follow—did I understand you to say, sir, that the Russians are not using Eastern Europe as their own sphere of influence and occupying most of the countries there and making sure with their troops that it’s a Communist zone, whereas on our side of the line the Italians and the French are still flirting with the possibility of Communism?”

Ford dug in: “I don’t believe, Mr. Frankel, that the Yugoslavians consider themselves dominated by the Soviet Union. I don’t believe that the Romanians consider themselves dominated by the Soviet Union. I don’t believe that the Poles consider themselves dominated by the Soviet Union…”—and when it came time for Carter to respond, he practically giggled: “I would like to see Mr. Ford convince the Polish Americans and the Czech Americans and the Hungarian Americans in this country that those countries don’t live under the domination and supervision of the Soviet Union behind the Iron Curtain.”

Ford’s coaches had implored him: no matter what Jimmy Carter said, he need only underscore the words peace and experience. “He could have answered every conceivable question with just those two things,” Ford’s media advisor Doug Bailey sighed ruefully to a reporter later. Bailey paused for a long time, then shrugged. “I guess he froze.”

Had he? At first, Ford’s political people didn’t think they had a crisis on their hands. Dick Cheney, keeping score backstage, thought his man had won nine questions to five; Ford’s debate coach scored it fourteen to zero. And according to Bob Teeter’s first poll, 11 percent more viewers thought Ford was the winner than named Carter. Henry Kissinger, however, thought differently. In his customarily obsequious manner, he told Ford he thought he’d done marvelously—then screamed to his protégé Brent Scowcroft that playing down Soviet domination of Eastern Europe was a political disaster. He was correct. Almost immediately, commentators began latching onto Ford’s “no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe” formulation as a bubbleheaded misstatement, a “gaffe”—evidence that Ford was losing a step.

The facts were more complicated. Ford was speaking accurately about a complex reality on the ground. Conservatives described the nations occupied by the Soviet Union after World War II as an undifferentiated mass of “slave states.” But Poland had resisted Russian control to a sufficient degree that Eisenhower granted it most favored nation trade status. (Joseph Stalin himself had supposedly observed that trying to impose his will on Poland was like trying to saddle a cow.) Kennedy said America should “seize the initiative when the opportunity arises” to reward Communist Bloc states for good behavior. Richard Nixon said Eastern Europe countries were “sovereign, not part of a monolith.”

This was why Ford refused to apologize for what he saw, at worst, as an infelicity of expression. But reporters kept pestering him. Eastern European ethnic leaders—who had prevailed upon Congress in 1959 to establish a Captive Nations Week observance every July—piled on, too. “Our people do usually vote Democratic,” said Aloysius Mazewski of the Polish American Congress, “but we were aware that many of them were not enthusiastic about Carter and were going to vote for President Ford. I think many of them will go back to the Democratic side now.” Carter said Ford’s words “disgraced our country.”

That was the interpretation that stuck: “After twenty-four hours of being told it was a bad mistake,” Ford’s White House spokesman Ron Nessen lamented, “the public changed their minds.” Teeter took another poll in which respondents gave the victory to Carter by a margin of 45 points. Ford had dared complexity where simplicity was supposed to reside. But with the joke circulating that people were hoarding “Poles for Ford” buttons as collectors’ items, and Carter’s running mate, Walter “Fritz” Mondale, joking that he could now drink for free in Polish bars, Ford surrendered. He called Mazewski with a groveling apology. They said this election was about forthrightness. But, plainly, not too much.

IT WAS AROUND THEN, HIS campaign rocked on its heels, that Gerald Ford’s people began contemplating a new sort of Southern strategy—with religion, not race, at its center.

Back in August, at a strategy meeting, Bob Teeter had recited the findings of a Gallup poll: 39 percent of Americans said they’d had a life-changing experience of the presence of Jesus Christ at a time and place they could identify, 72 percent read the Bible regularly, and 71 percent thought political leaders should pray before making decisions. “We’ve got to have Billy Graham on the ticket,” Doug Bailey replied. His partner, John Deardourff, nominated TV faith healer Oral Roberts. Someone suggested Ford could perform a small miracle at the Republican convention. Teeter warned them not to joke. “It could be the most powerful political force ever harvested.… They’ve got an underground communications network. And Jimmy Carter is plugged right into it.”

Then the next month the Almighty bestowed upon Gerald Ford a miracle—that Playboy interview.

“Evangelicals Seen Cooling on Carter,” read the Washington Post front page on September 27. It recalled an address the previous June at the annual meeting of America’s largest Protestant denomination: Southern Baptist Convention president Reverend Bailey Smith, who pastored an Oklahoma church with ten thousand members, said the country needed a “born-again man in the White House.” Some shuddered; Southern Baptists, the Post pointed out, “customarily prided themselves on their neutrality in political matters, on the non-hierarchical organization of their denomination.” But others were thrilled—and gave him a standing ovation when he roared next, “And his initials are the same as our Lord’s!” Now, however, Smith said he wasn’t even sure he’d vote for Jimmy Carter.

It had become apparent that Carter was an awkward fit with his coreligionists. He talked about legalizing marijuana. And appreciated liberal theologians. And palled around with Bob Dylan and the Allman Brothers; he was just not one of us. The SBC had been officially founded in 1845 after the national Baptists forbade slave owners from serving as missionaries. In 1918, an influential statement of the denomination’s mission, The Call of the South, argued that God had let the Confederacy lose the Civil War in order to steel Southerners to rescue the rest of the nation from the “new gospel of ‘tolerance,’?” the “false faiths” of “rationalism” and “liberalism”—“Antichrist teachings under the guise of religion.” Now more and more Southern Baptists were returning to these reactionary roots, making activism against feminism, homosexuality—and pornography in magazines like Playboy—part of their spiritual calling.

The bicentennial year was the watershed. Jerry Falwell, the Southern Baptist televangelist, staged “I Love America” rallies in 141 cities, frequently on the steps of state capitol buildings, starring fresh-faced undergrads from his own Liberty Baptist College, who sang patriotic songs accompanied by what they called “stage movements.” (Dancing was a sin.) In 1965 he had published a widely distributed sermon aimed at Martin Luther King Jr., arguing, “Preachers are called to be soul-winners, not politicians.” But now, at these rallies, his fiery sermon concluded with a line from II Chronicles that joined civic and theological vocations seamlessly: “If My people, which are called by My name, shall humble themselves and pray, and seek My face and turn from their wicked ways; then will I hear from heaven and will forgive their sins, and will heal their land.” Then, he would duck inside the marble halls to lobby.

A Fairfax, Virginia, minister named Robert Thoburn, author of How to Establish and Operate a Successful Christian School, whom conservatives admired because his own school was a for-profit business, ran unsuccessfully for Congress. So did the president of a fundamentalist college in Hammond, Indiana, Reverend Robert Billings, author of A Guide to the Christian School. A congressman from Arizona, John Conlan, together with Bill Bright of the Campus Crusade for Christ, began Third Century Press, which published books like One Nation Under God, by Rus Walton, which averred, “The Constitution was designed to perpetuate a Christian order.” Their organization, the Christian Freedom Foundation, sent 120,000 ministers pitches to join “Intercessors for America,” whose membership benefits included Walton’s book The Five Duties of a Christian Citizen and a manual about how to elect “real Christians” to office by adopting a familiar Christian activity—home Bible study sessions—to organize precincts. Explained Conlan, “The House of Representatives, which is composed of 435 members, is controlled by a simple majority of 218. At this time, there are at least 218 people in the House who follow in some degree the secular humanist philosophy which is so dangerous to our future.”

Conlan ran for the Senate. His primary opponent was Jewish. One of his slogans was “A vote for Conlan is a vote for Christianity.” Barry Goldwater, whose father was born Jewish, and Goldwater’s best friend, Harry Rosenzweig, the Jewish former chairman of the Arizona Republican Party, abandoned Conlan. He lost, left Congress, and threw himself into evangelical political organizing full-time. His ally Bright raised $25,000 each from twenty Christian businessmen, like Richard DeVos of the Amway Corporation, to purchase a Louis XIV–style mansion that had previously been inhabited by Washington D.C.’s Catholic archbishop, anointing it the “Christian Embassy.”

Bright and Conlan insisted their efforts were nonpartisan and non-ideological: anyone was welcome to join. Then, the liberal evangelical magazine Sojourners published an exposé revealing that their organizing manual suggested screening candidates with the question “How do you feel about Nelson Rockefeller or Ronald Reagan as presidential candidates?” (A preference for the tribune of the Republican Party’s liberal wing was disqualifying.) Bright insisted, “Campus Crusade is not political—in twenty-five years it has never been.” But the article also quoted him as saying in Campus Crusade’s magazine Worldwide Challenge, “There are 435 congressional districts, and I think Christians can capture many of them by next November,” and Conlan’s opinion of the Senate’s two proudest evangelical Christians, Mark Hatfield and Harold Hughes—who were liberals—“These are not the kind people we want in government. We don’t even want them to know what’s going on.” Sojourners’ editor, Jim Wallis, complained that Bright and Conlan’s project “gives an excuse for a lot of evangelicals who would like to find a reason not to vote for a Christian they perceive as a Democratic liberal.”

The cascading damage from the Playboy interview suggested Wallis was right. A preacher from Pennsylvania said of Carter, “I do not feel he has been ‘born again.’… He approves of social drinking.” Jerry Falwell—whose Old Time Gospel Hour aired Sundays on 260 television stations, “sixty-five more than Lawrence Welk,” the Washington Post noted—announced, “Like many, I am quite disillusioned.… Four months ago most of the people I knew were pro-Carter. Today, that has totally reversed.”

The Carter campaign, busy reaching out to Democratic interest groups from feminists to homosexuals to union members—and Playboy readers—took the evangelical vote for granted. The crisis exposed a political Achilles’ heel: Carter’s success so far had been built on seeming to be all things to all constituencies—constituencies often at war with one another. Now, for the first time, a bill for this ideological profligacy came due—and the Ford campaign spied opportunity.

AT FIRST THE PRESIDENT, A staid Episcopalian, was reluctant to talk about faith; the campaign pressed the message via surrogates, like Ford’s seminarian son Mike, who said, “Jimmy Carter wears his religion on his sleeve but Jerry Ford wears it in his heart,” and released Ford’s private letter to an evangelical film producer named Billy Zeoli: “Because I trusted Christ to be my savior, my life is His.”

Then, Ford stuck his finger in the wind, and took the plunge himself.

Shortly after the foreign policy debate, Ford hosted thirty-four evangelical leaders—proprietors of telecasts like Back to the Bible and The Hour of Freedom, executives from Billy Graham’s ministry and the Campus Crusade for Christ, Christian radio station owners, publishers, Bible college deans—for seventy minutes in the cabinet room. The star attendee was a preacher who’d first come to the nation’s attention after Brown v. Board of Education, when he demanded, “Don’t force me by law, by statute, by Supreme Court decision… to cross over in those intimate things where I don’t want to go. Let me build my life. Let me have my church. Let me have my school. Let me have my friends. Let me have my home. Let me have my family. And what you give to me, give to every man in America and keep it like our glorious forefathers made—a land of the free and the home of the brave.” He also said the movement for racial integration was “aching of idiocy and foolishness,” that the “idea of the universal brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God is a denial of everything in the Bible,” and that civil rights activists were “a bunch of infidels, dying from the neck up.” He claimed to have never seen a movie in his life and never intended to—until an actor named Ronald Reagan persuaded him that not all of them were sinful. (“I’m going to start going to some movies, and I’ll tell my congregation that it’s not a sin to see certain types of movies.”) His name was Dr. W. A. “Wally” Criswell, and, Ford’s campaign manager James Baker explained, “he’s acknowledged as a leader not only among Southern Baptists but among evangelicals”—apparently unaware that “Southern Baptist” was a subset of evangelicals.

In 1960, when his First Baptist Church in Dallas had some fourteen thousand members, Criswell led a national day of prayer against the ascension of a Catholic to the White House—which would “spell the death of a free church in a free state and our hopes of continuance of full religious liberty in America.” In 1968 he became the president of the Southern Baptist Convention. By 1972, he had come around on the question of segregation—but thundered so angrily against Richard Nixon’s opening to Communist China that the president invited him to the White House to talk him down. In 1975, when Betty Ford praised legalized abortion on 60 Minutes and took in stride the idea of her teenage daughter having a premarital affair, Reverend Criswell made national news again. “That’s a gutter-type mentality,” he said. “That’s animal thinking.” In the summer of 1976, he approvingly predicted a huge evangelical showing for Carter.

Then he and his colleagues met with the president in the cabinet room. Ford explained that his religion had “a tremendous subjective impact” on his decision-making, that he had “a deep concern about the rising tide of secularism,” and that he and Betty read the Bible each and every night. Impressed, Criswell invited the president to pray in his church.

IT COINCIDED WITH A FINAL pivot in Ford’s electoral calculations. Carter held Texas by only a thread. Ford strategists had originally planned to concentrate on states like New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Illinois—the “big industrial states of the North,” in the political reporters’ cliché. Now they changed their mind. Which meant they were catching up with the electorate. For the “big industrial states” were no longer, comparatively, so big.

A 1969 book by Nixon aide Kevin Phillips, The Emerging Republican Majority, had been the first and most influential codification of the argument: the way forward for the Grand Old Party was exploiting conservative sentiment in the South and Southwest—the “Sun Belt.” Demographic shifts informed the judgment. Changes in the number of votes states cast in the electoral college—calculated by adding up how many seats a state was apportioned in the 435-member House of Representatives plus each state’s two senators—tell the story. In 1948, the year Ford was first elected to Congress, New York got forty-seven votes. In 1976, New York cast forty-one electoral votes. Pennsylvania went from thirty-five to twenty-seven, Illinois from twenty-eight to twenty-six. Meanwhile Florida’s electoral votes doubled, Arizona’s went up by half, and California replaced New York as the nation’s most populous state. Reasons included the spread of air-conditioning, the Sun Belt’s salubrious “business climate”—a term coined by General Electric executives in the 1950s to describe municipalities with low wages and weak unions—and the ballooning military-industrial complex, which appreciated a salubrious business climate, too: between 1950 and 1956, New York lost more than a third of its share of prime Defense Department contracts to the Sun Belt. Sun Belters were prickly about the Northeasterners who behaved as if the world still revolved around them—Texans most of all. So it was that, reviewing these facts in the context of Carter’s LBJ gaffe, and Ford’s success with the evangelicals, Ford’s strategists scheduled a tour of the Lone Star State for the crucial second week in October, with Reverend Criswell’s giant red-brick church as the first stop.

The interior was festooned with banners depicting Revolutionary War soldiers and Bicentennial thirteen-star flags. Criswell’s hair was slicked back; he wore a cream-colored suit. He regaled his congregation with the story of his White House visit: “Mr. President,” he recalled asking, “if Playboy magazine were to ask you for an interview, what would you do?” Ford replied, “I was asked by Playboy magazine for an interview, and I declined with an emphatic ‘No’!” Six thousand worshippers broke into a torrent of applause.

Then he berated Carter for saying in another interview that he was considering removing tax-exempt status from church businesses like radio stations, TV programs, colleges, and publishing companies. Criswell said reading that brought “dread and foreboding to my deepest soul.… To tax any of them is to tax the church… leading to the possibility of our destruction.… I hear Gerald Ford, our president, say boldly and courageously that he would interdict any such movement in America. May the Lord give him strength!”

The president, sitting beside what the pool reporter called “a full orchestra larger than most Broadway pit orchestras,” beamed. The choir broke into Handel’s “Worthy Is the Lamb.” Criswell, described in the pool report as “organ-lunged,” remarked, “I think if Handel looked down from heaven, he would be proud of this choir and this orchestra. And Mr. President, that’s why the White House ought to be in Dallas, Texas, instead of Washington.” He described a speech President Ford gave to the Southern Baptist Convention as “one of the most moving and masterful addresses I have ever heard in my life.” Theatrically dabbing a tear from his eye, he described Ford’s seminarian son as “a sweet humble boy.” Then he called his White House visit “one of the highest days of my life.” The pair made their way down the aisle and out onto the church steps, where one of the waiting reporters asked if this meant the pastor was making a presidential endorsement. “Yes,” he said, fearing not for his church’s tax-exempt status. “I am for him. I am for him.”

FORD STUMPED ACROSS THE LENGTH and breadth of California, where the undecided vote was an astronomical 23 percent—and he did so sans the Golden State’s most prominent Republican, who cited a “prior commitment,” exactly the reason Reagan had given for neglecting to call on the White House during a recent visit to Washington. The “prior commitment” was a meeting with his political supporters at his ranch near Santa Barbara, an article in the Chicago Tribune titled “Reagan Snubs Ford Campaign in California” reported.

The final debate woke viewers up only when Carter offered an apology, of sorts: “Other people have done it and are notable—Governor Jerry Brown; Walter Cronkite; Albert Schweitzer; Mr. Ford’s own secretary of the treasury, Mr. William Simon; William Buckley; many other people. But they aren’t running for President, and in retrospect, from hindsight, I would not have given that interview had I to do it over again.”

The lowest percentage of the voting-age population since 1948, 55.5 percent, turned out on Election Day. “The public has the feeling of being nibbled to death by ducks, not addressed by giants as should be the case,” ABC’s Howard K. Smith said when it was finally over.

Mal MacDougall said, “If Reagan had been willing to really speak out for President Ford, really work for Ford, I feel convinced that we would have carried Texas. The same goes, of course, for Mississippi.” That would have covered sixty-six of the fifty-seven electoral college votes Ford required to win. Very few of the issues that would actually end up convulsing the nation over the next years had been substantively discussed. Another thing that found no representation in the media: that, at the same time the nation chose a Democratic president, conservatives were mobilizing with a passion, creativity, and energy never seen before.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (August 17, 2021)

- Length: 1120 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476793061

Raves and Reviews

"An absorbing political and social history of the late 1970s...The joy of this book, and the reason it remains fresh for nearly a thousand pages of text, is that personality and character constantly confound the conventional wisdom. Perlstein’s broad theme is well known, partly because he has made it so through his three earlier volumes (Before the Storm, Nixonland and The Invisible Bridge) on the rise of the New Right in American politics. In the 1960s and 70s, liberals overplayed their hand and failed to see the growing disaffection of Americans who felt cut out or left behind. (Sound familiar?) But Perlstein is never deterministic, and his sharp insights into human quirks and foibles make all of his books surprising and fun...The 1980 election marks the end of this book, and, Perlstein says in his acknowledgments, the end of his four-volume saga on the rise of conservatism in America, from the early stirrings of Barry Goldwater to the dawn of the Age of Reagan. One hopes Perlstein does not stop there. Reaganland is full of portents for the current day."—Evan Thomas, The New York Times Book Review

“The pointillist canvas of Reaganland is mesmerizing…Perlstein’s book certainly presents the fullest picture we have of the Reagan years.” —Thomas Meaney, The Nation

"Perlstein masterfully connects deep currents of social change and ideology to prosaic politics, which he conveys in elegant prose studded with vivid character sketches and colorful electoral set-pieces....The result is an insightful and entertaining analysis of a watershed era in American politics."—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

"If you don’t think a chronicle of the rise of conservatism in American politics can be just as entertaining and illuminating as A Song of Ice and Fire, think again. Perlstein, a local historian, wraps up his acerbic, thoroughly researched, and energetic series on the conservative movement with this tome covering the four years just before Ronald Reagan began his tenure at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue."—Chicago Magazine

“[M]ajestic…Perlstein sees American culture holistically, and his method is to implant you into the whole of a living tissue. Reaganland is so mammoth in scope and so scrupulously agnostic in presentation, each reader will likely find their own book in there. I walked away grateful for its larger arc.” —Stephan Metcalf, The Los Angeles Times

"One comes away from this book with a better understanding of how Carter was so thoroughly defeated....Perlstein casts a broad net, riffing on everything from Ted Bundy to New York Mayor Ed Koch, but that is part of the package here; by the end readers have more insight on the rising tide of conservative politics."—Library Journal

“A valuable road map that charts how events from 40 years ago helped lead us to where we are now.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

"At more than 1,100 pages, Reaganland is the fourth and final volume of Perlstein’s massive, sweeping history of American conservatism in the postwar era...Reaganland is terrific, a work whose characteristic insight and soaring ambition make it a fitting and resonant conclusion to Perlstein’s astounding achievement....Perlstein’s rapid-fire style of chronological narrative is riveting, like the world’s most exciting microfilm scroll...Perlstein’s epic series shows political history and cultural history cannot be disentangled." —Jack Hamilton, Slate