Get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

The day Uncle Goodwin “Buddy” Bush came from Harlem all the way back home to Rehobeth Road in Rich Square, North Carolina, is the day Pattie Mae Sheals’s life changes forever.

Pattie Mae adores and admires Uncle Buddy—he’s tall and handsome and he doesn’t believe in the country stuff most people believe in, like ghosts and stepping off the sidewalk to let white folks pass. But when Buddy is arrested for a crime against a white woman that he didn’t commit, Pattie Mae and her family are suddenly set to journeying on the long, hard road that leads from loss and rage to forgiveness and pride.

Excerpt

If you are reading this letter, you have found all my letters, all of my secrets. The secrets of Rehobeth Road and the secrets of Rich Square, North Carolina. Most of all, you know the truth about what happen to my uncle Goodwin “Buddy” Bush. Uncle Buddy wasn’t really my uncle. He was what Grandpa called kinfolks on nobody’s side. Just plain old kinfolks. Grandpa told me that Uncle Buddy had his own family a long time ago; a real ma and daddy. Blood kin! He was just staying with them while his folks Rosa Lee and Hersey worked in tobacco over in Rocky Mount. Rocky Mount ain’t far, just north of the riverbank, about thirty-five miles from here. Grandpa said that Uncle Buddy’s folks went to work one day and never made it back across that river. They were in some kind of accident in the tobacco barn and they both died on the same day. So my grandpa and grandma just kept Uncle Buddy and raised him like he was their own. He went North when he was sixteen. When he came back in 1942, he came home to us. I was seven years old. Blood kin or not there are few things about May 1, 1942, that I will ever forget. It was a Sunday when my uncle Buddy arrived. Ma let me stay home from church. My big sister and brother had to usher at church, so off they went. Me, I stayed home to lay eyes on him for the first time.

His car was blue.

Sky blue.

A Cadillac.

A new Cadillac.

His suit was blue too.

Dark blue.

With pinstripes.

Pinstripes like Grandpa’s Sunday go to meeting suit.

I remember standing there holding my breath.

And my pee.

I couldn’t leave that front porch.

The outhouse would just have to wait.

Lord, I wouldn’t have missed that first sight at my uncle for nothing on Rehobeth Road.

A city man.

He pulled that Cadillac right up to Grandpa’s front door.

I looked at his shiny shoes first. I could see my face in them.

I smiled.

My eyes went slowly up his legs.

They looked so long.

His jacket had

one

two

three

let’s see

six buttons.

His shirt was white.

His tie was a pinstripe like his suit.

Then I saw the hat.

I will never forget that hat.

Yes, blue with a feather to the right.

Only a city man could own a hat like that.

Grandpa stood beside me.

He never moved.

I stepped to the right.

Grandpa waited for Uncle Buddy to walk up to him.

He did.

“Welcome home, son.”

“It’s good to be home, Daddy Braxton.”

They hugged.

Grandpa looked over his shoulder at the Cadillac.

“Nice car, boy.”

“Oh, it ain’t much.”

Ma runs onto the front porch.

“Ain’t much! Bro, I ain’t never seen a car this fancy, never.”

“Hey, sister.” He smiled a big smile at Ma as she ran around his car.

She rubbed it like it was a genie bottle. Then she ran over to Uncle Buddy and jumped in his arms like she was a rag doll.

“Hey, Bro.”

That only left Grandma to welcome Uncle Buddy home.

“Come on in this house, boy. I been keeping your breakfast warm all mornin’.”

We all followed Uncle Buddy inside.

I saw Grandma cry for the first time when she hugged her only boy. The one that ain’t blood kin.

We ate.

We laughed.

We had a time.

We were a family.

• • •

I wonder if Uncle Buddy was thinking about his real folks that day. I hope he wasn’t sad. They must have loved him so, but Lord knows we love him too. I can’t imagine anybody loving him more than Grandpa did. More than me! I am glad he is my uncle and I wish he would come back to us. But he can’t because there still ain’t no telling what white folks might try to do to him. I don’t think Uncle Buddy will ever be able to come home again, so I just wrote about him in my letters to BarJean and on paper sacks around the house. When I was done writing the letters I mailed some of them to my big sister. Some of them, I hid in the old smokehouse in the backyard. Yes, I hid the truth. A lot of truth is hidden around here. If only the trees could talk or the dirt could sing.

I remember like it was yesterday when this whole mess that forced Uncle Buddy to leave us started. Sometimes when I think about what happened, I feel twelve again. That’s how old I was in June of 1947. I’m telling you I can just relive it like it’s happening now. Right now.

• • •

This June morning is no different than any other hot summer day on Rehobeth Road. The moon was full last week and I’m sure it is about to change all our lives, just as my grandma said full moons do. Last year when the full moon came my grandma said she saw death in that moon. Surely enough my cousin June Bug, my aunt Rosie’s boy, who was only ten, went ice-skating with no skates over on Jackson Creek. Well the ice was too thin and both June Bug and his cousin Willie on his daddy side fell in and drowned. They held a double funeral for them and everybody was crying.

Sad . . .

Sad . . .

Now every time a full moon comes, I just get scared, scared, scared. When the full moon came last week, I thought old man death would surely be back for another one of us.

To my knowledge every one of us with Jones blood are up this June morning clothed in our right mind. So I pray the full moon won’t bring no sorrow this time. I’m up early to pick cucumbers. It’s Friday and the heavens opened last night and let out enough rain for Ma to announce that we wouldn’t be going in the cotton field to chop today. We chop for Ole Man Taylor, who owns this land, this house, and most of Rehobeth Road. His great-great-granddaddy owned all of this land during slavery. He lets Ma plant whatever she wants on the land that he don’t use. Working our crops, not his, suits me just fine as I happily roll out of the bed. Softly, my feet touch the old sack that we use as a rug. Soft enough for me to not wake up Ma, who is sleeping across the kitchen in what we call Ma’s room. My room is the girls’ room, because that’s where my sister BarJean and me slept together when she lived at home. Her real name is Barbara Jean, but no one is called by their real name on Rehobeth Road. That includes me, who would prefer Patricia to Pattie Mae any day. There’s a boys’ room upstairs next to Uncle Buddy’s room. That’s where my big brother Coy, whose real name is McCoy, slept until he moved up North at sixteen back in 1945. So I guess it ain’t nobody’s room right now.

BarJean moved up North last year and she said she ain’t never living in these sticks again, never. So I guess this ain’t the girls’ room no more, it’s my room.

When I was really little, we all slept upstairs in this big old brown house. Not one drop of paint on it. By looking at it no one would ever know that rich white folks lived here first. When it was white, this house was the main house of the plantation. After the white folks left, the slaves moved in. That’s why we call it the slave house. But it was surely a plantation main house first. Taylor’s Plantation. It’s still carved on a silver bell that’s hanging from a tree in the backyard. Big letters—TAYLOR’S PLANTATION. Ma said during slavery that bell was used for ringing at feeding time. Not the animals, the slaves. I think that old bell is worth some money because Mr. Spivey, who owns the antique store over in Scotland Neck, has been trying to get Ma to sell him that bell for years. Ma told him, “You know I don’t own this house, so I shoo don’t own that bell. You need to ask Ole Man Taylor.” Mr. Spivey ain’t going to ask that mean man nothing, so that bell just hanging there reminding us of slavery.

Maybe revenge is sweet because my grandpa, Braxton Jones, who lives right down the road on his own land, said that the Yankees ran all them white folks away after the Civil War. He said the Taylors didn’t come back for years to claim this land. My grandma, Babe Jones, said, “Braxton don’t know what he’s talking about because he wasn’t even born then.” Grandpa said, “No, I wasn’t born, but I knows what my pappy Ben Jones told me.” I don’t know who’s right and who’s wrong, but Uncle Buddy said, “It don’t matter because don’t nobody but poor-ass niggers want this raggedy damn house now.”

He better not let Ma hear him say that after she let him move in with us when I was seven. Yep, right after breakfast the day Uncle Buddy arrived, he came home with us and never left. When he moved in, Ma packed all our stuff and moved us downstairs on top of each other like sardines in a can. Everybody except Coy. Just because he is a boy, he got to stay upstairs. There was plenty room upstairs for all of us. Ma says every day that God sends, that it don’t look right to folks here on Rehobeth Road for her to be sleeping upstairs with a man that ain’t blood kin. Raised in the same house and she talking about he ain’t blood kin. But she said Uncle Buddy is more than welcome here, because he gives her $35.00 a month for rent and food. That money goes a long way because he doesn’t eat here much. As a matter of fact, Uncle Buddy ain’t hardly here at all. He’s up at 4:00 and out the door by 5:00. Off to the sawmill in town where he been working since he arrived. He is the only colored at Quick’s Sawmill. I don’t think the white folks there like him very much, because he said they think all coloreds belong in the cotton field.

He told me the only cotton he picking is his T-shirt up off the floor. Uncle Buddy works half a day on Saturday, but he always hangs around in town to wait for me so we can have meat skins biscuits together while Grandma gets her grocery. That’s the only day a week I get to go into town other than school days. I am Grandma’s official grocery helper. She doesn’t know it, but Grandpa gives me a quarter every week for going with her. Grandpa doesn’t know it, but I would go for free just to be with Grandma and to go into town.

I best stop thinking about town and my quarter and get myself in that cucumber patch. I get myself past Ma. Past the old breakfast table with chairs that don’t match and out the door. I close it with ease and Ma never move. It don’t seem like nobody up on Rehobeth Road but me and my dog Hobo. Uncle Buddy gave him to me four years ago. He found him wandering around at the sawmill. Nobody claimed him for a month and he became my dog.

I don’t want to explain to Ma why I am trying to get these cucumbers off the vines so early. Ma thinks it ain’t never too hot to work. I prefer not to get too black, myself. But that ain’t my only reason for trying to beat the sun today. I want to finish my cucumbers and help Grandma with her strawberries all before 4 o’clock. That way I can rest before going into town with Uncle Buddy for my first picture show tonight. That’s right. We are going to the movie house for the first time in my life. My clothes are all laid out on the bed down the road at Grandma and Grandpa’s. I took them yesterday so I will be ready tonight. I’m wearing my blue and yellow checked skirt and my blue top. I hope Ma don’t say nothing about me wearing my Sunday go to meeting shoes on a Friday night. She definitely will, so I better get ready to hear her fuss. Uncle Buddy and me will be leaving right after supper. First things first. I got to get these cucumbers picked.

As I lean over to pick my first one, I remember the stick that Uncle Buddy made for me to use to push the vines back. I keep it hidden on the third row. That’s my row to pick, so I know Ma won’t find it. Nothing fancy, just a stick with a hoop on the end. Uncle Buddy said I was going to ruin my hands if I don’t stop working like a 1947 slave on this farm. If that happens, according to Uncle Buddy my chances of becoming a city girl are over. We talk about the North all the time. No matter if he was born here, my uncle Buddy is a New York man and you can tell it when he talks. He ain’t all-countrified like me and the rest of the folks on Rehobeth Road. He’s dress different even when he’s going to work. You could never know Uncle Buddy ain’t blood kin. He is tall like Grandpa and Coy; and as black as midnight. I’ve never seen teeth as white as his. And don’t nobody in Rich Square shine their shoes like he does. “You can tell a real man by the shoes he wears,” Uncle Buddy declares at least once a week. And he don’t believe in the country stuff we believe in, like getting off the sidewalk to let white folks pass by. Uncle Buddy don’t even believe in hanks. Folks on Rehobeth Road call ghost hanks. Uncle Buddy call ghost ghost and he don’t believe in them either. Yep, he’s a city man all right. For the life of me I will never understand why he came back five years ago. Nobody knows for sure. He just showed up that Sunday morning after writing a letter and didn’t say why he was coming or why he won’t be going back. BarJean claims she know, but I don’t think she know nothing. She claims some folks in Harlem said Uncle Buddy left because he could not have the woman he loved. A woman that belonged to somebody else. A light-skin woman! She claim Uncle Buddy heart was broken. I can’t imagine going North for twenty-two years, then moving back here. I definitely would not leave because I could not have some man. I would just find me a new one. That’s what Uncle Buddy should have done. Found him a new woman to love. A dark-skin woman! Anything except come back here. I live and dream of the day when I leave this place and go to New York. Not just New York, but to Harlem. Not even Ma can get into my dreams.

“Pattie Mae!”

Guess I spoke too soon.

That would be Ma. Trying her best to get into my dreams; yelling like I’m halfway cross the field somewhere.

“Mornin’ Ma.”

“Mornin’ my foot, what you doing in that field so early?”

I want to yell back, “Trying on my new diamond earrings.”

Ma ain’t much on people joking with her so I better not say that.

“Just trying to beat the sun.”

“Trying to beat the sun. Child, you can’t outrun God. You better stop listening to Buddy about that light-skin, dark-skin mess. Now come on this porch and wash your hands while I finish breakfast. I already put water in the face tub.”

Lord, when I get to Harlem I’ll be done with using face tubs. BarJean told me she got running water and yes, a bathroom. I put my stick down and Hobo and me slowly walk back to the slave house. I don’t know who use to live in it, but I know I feel like a slave this morning. Just look at this place, all run down. But Ma keeps it so nice and clean. Cleaner than them white folks’ yards in town. Probably cleaner on the inside too. They just got paint on the inside and the outside. This place ain’t seen no paint since the Civil War. The closer I get to the slave house I want to scream, “I hate these fields. Please, BarJean, take me North!” By the time I make it to the porch Ma has turned around and gone inside. But not before I notice she is wearing a dress. I hope that I will be as tall as she is when I’m a woman. I saw on some of her important papers that she is six feet tall. Tall and beautiful with skin the color of a brown paper sack and hair that has as many waves in it as a newborn baby. When Ma walks, all the men look at her hips that are round and shake like Jell-O. Mr. Walter Garris likes Ma’s hips so much that he screams, “Lord have mercy!” when she walks by. That makes Ma really mad. Uncle Buddy says I am going to be a pretty woman like Ma when I get older. He says probably not as pretty as Ma, because it’s a “Sinfore God to look as good as Mer Sheals.” Her name is Mary. Somebody replaced the “a” with an “e” and dropped the “y” years ago, just like they took “tricia” off of Patricia and added “tie Mae” to my name. That’s just how it is on Rehobeth Road.

So why is Ma wearing a dress? Surely she is going to pick cucumbers today. She always picks cucumbers when it rains. If she ain’t chopping, she picks cucumber every day from late May until they are all gone, from sunrise to sunset. Ma stops chopping in August in time to work in tobacco, because tobacco workers make $4.00 a day and we only make $2.00 a day chopping. But August nor tobacco are on my mind this year, because I will be on that train going to the unknown by then. This will be the first year that I am old enough to work in the tobacco field, like it is honor or something stupid like that to turn twelve and prime tobacco. That’s the rule on Rehobeth Road. You have to be twelve to work in the tobacco field. Myself, Pattie Mae Sheals, has other plans. Besides, Uncle Buddy says people who chop and prime tobacco ain’t nothing but $2.00 a day slaves.

I stop on the back porch and wash my hands in the white face tub that Ma left there for me. Old like everything else around here. Clean like everything else around here. The smell of her biscuits reaches my nose before I reach the back door that is falling off the way it does at least ten times a week. I’m sure Grandpa is coming up here with his toolbox and fix it as soon as he gets around to it. He has been a bit under the weather, so I don’t want to mention the door to him again. No need to tell Uncle Buddy because it’s dark when he leaves home and dark when he comes back. Ma never complains about what Uncle Buddy don’t do around here. I guess that $35.00 a month includes Ma fixing things too. Ma swears that money keeps us out of the poorhouse. If this ain’t the poorhouse, I don’t know what is.

Inside the slave house, in the kitchen, on the table I notice Ma’s black leather bag. The one that her oldest sister, my aunt Louise, brought her all the way from Harlem. I also notice that Ma doesn’t have on just any dress; she has on her Sunday go to meeting dress. She would never dress like this during the week, unless she was going to a funeral or the relief office over in Jackson. Lord have mercy, I just want to ask her why she is all dressed up, but Ma says that children ain’t suppose to ask grown folks questions.

That’s another rule on Rehobeth Road. “Don’t ask grown folks no questions.”

I know I really don’t have to. All I have to say is “Ma, you look so pretty.” And she does. Even if she don’t, Uncle Buddy says never beg a woman. “If you tell her she looks good, she will tell you anything you want to know.” Stuff like “Honey, honey you fine as you want to be” and “Baby, you the sugar in my coffee.” Now that’s the kind of mess Uncle Buddy says he used to tell them gals up in Harlem. I don’t know about them city women that Uncle Buddy knows, but Ma loves a compliment. So I just take my seat at the end of the table, next to the stove, where I have been sitting since Ma took me out of the high chair. The high chair we sold back to the thrift shop in Jackson when I got too big for it. Ma has prepared the usual two eggs, two pieces of bacon, and one biscuit. No milk, just water from the rusty well in the backyard.

“My, you look pretty today, Ma.”

“Well, thank you, child. I thought I would get dressed early. Mr. Charlie will be here soon.”

Ma would not be dressed like this just because Mr. Charlie is coming by. He comes by all the time. Mr. Charlie and his wife, Miss Doleebuck, are Grandpa and Grandma’s neighbors and best friends. At seventy-five, the same age as Grandpa, Mr. Charlie has a car. A 1935 Chevy. That’s it. The car! Mr. Charlie and Ma are going somewhere, but I have to find out where.

“I told you to eat your food. Mr. Charlie will be here in a minute. Now hurry.”

“He will?” I say, trying not to ask a grown folks question.

“Yes he will. I’m going into town with him and your grandpa. He’s taking Poppa to see Dr. Franklin.”

“Doctor?”

No time to follow some silly rule about not asking grown folks questions. I want to know why Grandpa is going to the doctor.

“Why?” I ask as tears run into the eggs that I don’t want no more.

I know Ma is getting ready to say, “Don’t ask grown folks questions,” until she sees the tears in my eggs.

“Now why are you crying, child? You know Poppa hasn’t been feeling well for a while. And what did Buddy tell you about crying all the time?” If I tell her what he really said she would give him a tongue-lashing as soon as he steps foot in this house. But what he really said was “Crying makes you piss less.” I can’t repeat that, so I say, “He said big girls don’t cry.”

Ma smiles and say, “He’s right. Now, hurry.”

Ma’s mighty out of herself this morning. She just rushing and fussing. She must be some kind of worried about Grandpa. He is definitely a little under the weather, but he must be really sick to go to a doctor. I figure that he has drunk enough of Grandma’s leaves from the woods to feel better by now. Grandma claims she has a cure for everything. Puttin’ tobacco on your chest for a sore throat. A penny around your neck to stop a nosebleed. A broom at the door so the hanks won’t ride your back at night and roots from the grass of the unknown for colds. And she has birthed as many babies in Rich Square as Dr. Franklin, the white doctor. She brought BarJean, Coy and me into this world and most of the children here on Reheboth Road. She nurses most of the grown folks on Rehobeth Road too, except Uncle Buddy. He says, “Never in this world.” As a matter of fact, Uncle Buddy don’t trust no doctors around here. He drives all the way to Harlem twice a year to see his city doctor. There have been a lot of talk on Rehobeth Road about a new colored doctor coming to town. Not Rich Square, but Potecasi and that ain’t too far. I guess that place is about ten miles away. Can’t worry about a colored doctor that might come later. I want Ma to tell me about the white doctor that’s here now and why Grandpa is really going to see him.

Ma still in deep thought, she doesn’t say a word for a minute.

“Ma, I guess Grandma’s medicine ain’t working.” I’m trying my best to get her to talk. She looks like she wants to laugh at my belief in Grandma’s homemade medicine. Like the time I couldn’t stop pissing in the bed and she boiled me some green stuff to drink for a month. Ma said that it wasn’t that stuff that worked. She is probably right and it was her threats of beating my skin off if I didn’t stop messing up her sheets that did. I just didn’t understand why Ma went through all the pain of having me and then she planned to beat my skin off. Anyway, I want to know what is happening with Grandpa. My grandpa!

“Don’t you worry about Grandpa. He just has a slight cold.”

I can’t believe she just said that.

A churchwoman lying. Lord have mercy!

“Slight cold? It’s June.”

Ma ignores me as she takes her old blue apron off and hangs it on a nail behind the kitchen door that don’t have paint on it either. Then she sits down and takes off her bedroom slippers and puts on her black Sunday go to meeting shoes.

“Can I go with you to town? I want to see Grandpa.”

“No you cannot. You have to go and help your grandma pick strawberries. She is waiting for you.”

Grandma’s strawberry patch is as big as our cucumber patch and she sales them at the market every other Saturday as fast as we pick them. Sometimes folks, even white folks, come by the house to buy them by the basket. She only charges a dollar a basket. I overheard Uncle Buddy telling Grandma she should charge more for her big, pretty strawberries. She quickly told him he should mind his business. “Folks round here don’t have that city money like you made in Harlem, boy.”

End of that!

Ma reaches in her bag and pulls out my letter from BarJean that probably arrived yesterday, but she forgot to give it to me. She forgets sometimes and I have to ask for my Thursday’s mail. Rain, sleet, or snow, my letters come from BarJean every Thursday that the Lord sends. Always on blue stationery in a blue envelope and always on Thursday. As she gives me the letter, I hear Mr. Charlie’s car horn blowing like he is running from a fire.

Before Ma can say, “Sit back down and eat,” I grab my letter, stuff it in my pocket, and run out of the door. Surely, she is not going to forget that I grabbed that letter out her hand. That will get me one lick or no TV at Grandma’s house for a week. Don’t have to worry about the TV around here. We don’t have one. Uncle Buddy says he don’t care what Ma says, he’s giving me a TV for Christmas.

Mr. Charlie is waving as I run down the long path trying to get to the car before Ma can even get her purse off the table. I want a minute alone with two of my three favorite men. Uncle Buddy is the third, of course. Actually they are the only men in my life. Uncle Buddy said my daddy, Silas Sheals, ran off with Mr. Charlie’s gal Mattie when I was a baby. He also said that my daddy and Mattie got themselves a new baby girl named O’Hara. Named after that white woman Scarlett O’Hara from Gone with the Wind. Ma don’t ever say nothing about my daddy and Mr. Charlie and Grandpa somehow managed to stay friends. Now Miss Doleebuck dares my daddy to dot in her door and the same goes for Mattie if she wants to bring him with her. So Mattie only comes on holidays and Silas Sheals don’t show his face at all. Miss Doleebuck said they both are a disgrace. Grandma said, “Disgrace my foot, Mattie is a slut.” I’m almost sure that Grandma is going to tell me what a slut is as soon as I am older.

I tell you one thing, if she don’t tell me, Uncle Buddy will. All I got to do is ask him.

I pull the car door open and jump in Grandpa’s lap.

“Hey, gal,” he and Mr. Charlie say at the same time.

“Hey, Mr. Charlie. Hey, Grandpa.”

Grandpa don’t look the way he did yesterday. He is dark compared to his light skin that usually look like a cake of butter from their old cow that I named Sue. The poor cow was nine years old and didn’t even have a name until last year. Rooms on Rehobeth Road got names, why can’t the cows?

“Are you okay, Grandpa?”

“I’m all right, child. How you this mornin’?”

“I’m fine. I got up really early today.”

“Is that so? And why did you do that?”

“Well the ground too wet to chop, but I picked a basket of cucumbers. I’m trying to sell a lot so that I will have extra money when I go North. Uncle Buddy said there’s lots of stuff to buy in Harlem.”

“He did, did he? And just where is Buddy this morning?”

“Working as usual. But he is taking me to the movie house tonight.”

Grandpa said he was never going to that theater as long as colored folks have to go in the back door. But he is glad that I am going.

“Well, that will be nice.”

“You aren’t going anywhere if you don’t get your tail off of Poppa so that we can leave.”

The voice of trouble have caught up with me.

Ma has made it down our long path and she looks so pretty as she give me the look.

“Leave her alone, Mer. She just saying good mornin’.”

Thank God, Grandpa is coming to my defense. Not that Ma is listening. She says Grandpa can’t raise her children. Now she says that to me, not to Grandpa. She don’t do no talking back to Grandma or Grandpa even if she is forty-eight.

“Fine, but we have to go.” Now she’s giving me the “I’m going to tear your tail up later” look.

I ease out of the car and stand on the wet grass hoping Ma will let me go.

Instead she starts giving me orders for the rest of the day.

“Now you know you can’t stay home by yourself. Go on up to Ma Babe’s and I will come there when we leave Dr. Franklin’s.”

That’s what Ma call my grandma, “Ma Babe.”

“But I haven’t taken my bath yet.”

“You don’t need a bath. You are going straight to the strawberry patch.”

“Bye,” I say as I wave.

They wave back as Ma points her finger, saying something. Who knows what. I will have to talk to Ma later when Grandpa and Mr. Charlie ain’t around. I know she knows I’m becoming a woman and I’m getting too old not to wash up before leaving home. I don’t know when, but soon I know I’m going to get my period just like Denise and Sylvia at school did. Denise told me she was sick as a dog when Mother Nature came to visit her the first time. Sylvia said she didn’t hurt at all. Accordingly to the conversation I overheard between BarJean and her best friend Boogie, Miss Doleebuck’s granddaughter, the only reason Sylvia didn’t hurt when she got her first period is because she had been messing with boys already. What a horrible thought. I think Sylvia might be a slut, too, like Mattie. Denise, Sylvia and me suppose to be best friends at school. But I like Caroline much better than both of them. We call her Chick-A-Boo. She lives right down the road. She is my real best friend. Those other girls are not like us. They are town people. They got more than two pairs of shoes and they have daddies. Beside, they spend all their time talking about boys. Uncle Buddy has already warned me to stay away from boys. He said they will give me worms. God forbid what that means.

I just pray we move into a house with a bathroom before my period comes. I don’t want to use the outhouse for such personal matters. But I’ll worry about my period when it comes.

Right now I just want Grandpa to get well. I feel like crying just thinking about Grandpa going to the doctor. Specially Dr. Franklin. Now Grandpa don’t know that I know this, but one day when I was fishing with Uncle Buddy over in Jackson Creek, he told me that Dr. Franklin and his brother Eddie, who is the sheriff, had mistreated Grandpa about thirty-five years ago. See, before the Holy Ghost came and saved Grandpa one Sunday morning at Chapel Hill Baptist Church where he has been attending for fifty years, he would go into town and drink in what colored folks called “the bottom” on Saturday nights. It was really an alley where the colored men would get together every Friday and Saturday night to play cards and enjoy their moonshine. Grandpa said he had a mason jar of moonshine too many when he decided to go home before Grandma came looking for him.

Just as he tried to climb into his old pickup truck, the sheriff stopped him.

“Where you going, boy?”

“Home, Sheriff Franklin. Just heading home.”

“Not tonight, you ain’t!”

Grandpa was more than willing to sleep the moonshine off in jail. But that old mean sheriff took it upon himself to hit Grandpa over the head with his billy club before arresting him. Knocked Grandpa cold and threw him in jail. Uncle Buddy said Grandpa was convinced that Dr. Franklin, whose office was upstairs from the jail, knew he was hurt and didn’t come to see about him until morning. Both them Franklin boys are mean. Now if Grandpa even mentions their names, he’ll say, “Yes, evil and evil sleep in the same bed.”

When Dr. Franklin finally checked on Grandpa just before day, he wrapped his head in some bandages and let him drive himself home. Well it turned out Grandpa had a brain concussion (whatever that is) and he drove his old red Ford right into a tree down on Brown Hill Road. Grandpa passed out and slept for hours. By seven in the morning, Grandma and Miss Doleebuck headed out on foot searching for their husbands. Yes, Mr. Charlie was in the cell next to Grandpa the night before for no reason at all. They just arrested him for coming to the jail to look for Grandpa.

They released Mr. Charlie later on that day when Boogie’s mama, Fannie Mae, went down to that jail and cussed them out like they weren’t even white folks. Around 8:30 that morning, Grandma and Miss Doleebuck made it to Grandpa’s truck where he was still passed out. It took them a while to wake him up, and when they did they had to walk all the way home. Poor Grandpa started having blackouts after that and he never took another sip of moonshine. Been saved and sober ever since.

The other thing Grandpa don’t know is Uncle Buddy told me that although he was little he remember the whole thing. He also don’t know that Uncle Buddy and some of his friends, Lennie, Hosea, and Earl, went out to town that next weekend and put holes in every Franklin car tire that they would find. They sure did. That’s what Uncle Buddy said and I believe him. Mercy to the highest, it’s nice to have all this grown folks business at twelve.

I better stop thinking about all of this before I reach Jones Property because Grandma can read your mind. Now she is a piece of work. I swear that woman knows what I am thinking before I do. Smoke coming from the chimney in the kitchen at Grandma’s house and I know she has not put out the breakfast fire yet. Thank God, she’ll cook me some breakfast, I’m thinking, as I walk faster. I can’t make it till noon without food.

That pleasant thought ends quickly when I find myself face to face with the bulls from Mr. Bay’s dairy. He is Grandpa and Grandma’s neighbor and compared to us, Mr. Bay is a rich man. Rich and mean. I don’t think he like colored folks very much and he laughs every time one of us forget and wear red while passing his terrifying bulls. Today that would be me. There is a big fence between me and the bulls, but I am still afraid to run, because I know they will run all the way down the fence with me. That alone scares me to death. Uncle Buddy walks by here whenever he wants to, wearing blue, red, whatever colors he please. He says, “I ain’t scared of no damn bull. I’m going to eat them for dinner one day. They ain’t going to eat me.”

I can’t run if I want to since my dear sweet ma locked me out of the house in my bare feet. I want to stick my tongue out, but that’s red too.

I walk in slow motion as the mama cows join the bulls at the edge of the dairy farm field. There must be fifty all together.

I finally reach the path that divide Mr. Bay’s dairy from Jones Property. I am still nervous when I reach in my pockets and feel my new letter from BarJean. The bulls have scared me so bad that I almost forgot I had it. I stop at the pecan tree to catch my breath and to read my letter. Grandpa planted this tree forty-eight years ago for Ma. The day she was born. He calls it Mer’s tree. In the back there are trees for her sisters, the Louise tree and the Rosie tree. Yes, Uncle Buddy has a tree too, right over there at the pond. Since he ain’t blood kin, Grandpa just took Uncle Buddy for a walk when he was ten and let him pick out his own tree on Jones Property. The day I was born Ma said Grandpa went right outside and planted my tree. But the Pattie Mae tree ain’t big enough to sit under yet. So I’ll just set under Mer’s tree to read my letter.

The paper is blue like always and it smells like BarJean’s favorite perfume. I can hardly wait to sit down as Hobo, who has followed me all the way, lies down beside me. The words make me feel closer to the North that I will soon see.

Dear Pattie Mae:

How are you, Ma, Grandpa, Grandma, and Uncle Buddy doing? I am doing fine and so is Coy. You know we have been sharing an apartment together all year. Well, the big day has come and I am moving into my own place down on 125th Street. Your big brother has met a really nice girl and they are getting married. That’s right! Now you will have two big sisters.

Guess what? Her name is Mary, just like Ma’s. Isn’t that nice?

Now you have to keep this whole marriage thing a secret and not tell Ma. Coy wants to tell her himself. So be a big girl and don’t tell her. Okay?

My dear little sister, I’m glad you want to come here in late August.

I have to go now and I am looking forward to seeing you soon. You, my dear sister, will be my first guest in my new apartment.

Love, your big sister

BarJean

Coy is going to get married! More importantly, BarJean trust me enough to tell me a secret.

I put my letter back in my pocket and tuck my secret in the back of my mind. At least until I see Grandpa. I’ll tell him and he will tell no one. Difference from me.

I stick my tongue out at the bulls that are far away now and start walking as fast as my legs can carry me to get me some breakfast.

Reading Group Guide

Join our mailing list! Get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

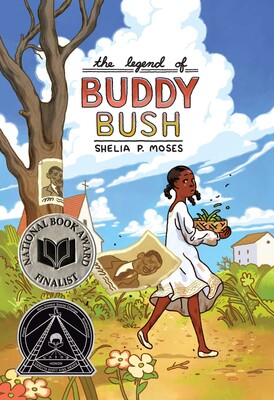

The Legend of Buddy Bush

by Shelia P. Moses

Discussion Questions

1. What was life like for African Americans living in the South in the 1940s? How were African Americans treated? What rights did they have? What rights were they denied? What was happening in the United States, and the world, at the time The Legend of Buddy Bush takes place? Does The Legend of Buddy Bush accurately portray the social, economic, and political climate of the United States during the 1940s? Give examples to support your answer.

2. When Pattie Mae asks Uncle Buddy why they have to sit in the balcony at the movie theater, he explains: "The same reason we had to buy our tickets in the back and eat last month's ice cream. We have to sit up here for the same reason that lady yelled at me like I was trying to hurt her." What does he mean? Explain, in your own words, the reason Pattie Mae and Uncle Buddy have to sit in the balcony. What other rules must the African American residents of Rich Square obey? Who made these rules, and why? By whom are they enforced? What are the consequences for violators? Did these same laws exist in New York and other northern states during the 1940s?

3. How has the experience of living in Harlem impacted Uncle Buddy's life in Rich Square? How did life in the North affect his views on race relations in the South? Do you think Uncle Buddy would have been accused of rape if he had not lived in the North?

4. "Sometimes I feel like the only reason I was born into this world is to wash dishes, pick cucumbers, and chop," says Pattie Mae. "Uncle Buddy said that it is all post slaves stuff that I am doing around home and on Jones Property." What does Uncle Buddy mean when he calls Pattie Mae's work "post slaves stuff"? Give examples of and describe the work done by Pattie Mae and her family. How does the legacy of slavery affect the work life of Rich Square's black citizens?

5. What role does religion play in the lives of Rich Square's African American residents? Explain the importance of the church. Give examples of how church members join together in support of Buddy Bush and the Jones family.

6. Pattie Mae dreams of living in Harlem. When Grandpa dies she finally gets her chance. "I hope it is just as beautiful as in my dreams," she says. What does Pattie Mae think Harlem will be like? Will her expectations match the reality? Why or why not? How will life in Harlem be different from life in Rich Square? What adjustments will Pattie Mae have to make as she goes from a rural environment to an urban environment? Will Pattie Mae stay in Harlem or will she eventually come back to live in Rich Square? Explain.

7. Shelia P. Moses uses a literary device called dialect to draw readers into the story. What is dialect? Give examples from the book. How would The Legend of Buddy Bush have been different if it was not written in dialect? Would it have been as effective? Explain. Give examples of different American dialects and other books you have read that use dialect.

8. Why do you think The Legend of Buddy Bush was selected as a Coretta Scott King Honor Book? Remember, the CSK Award recognizes books that offer a message of peace, nonviolent social change, brotherhood, and honor. Give examples of the ways in which The Legend of Buddy Bush fulfills these four pillars of the CSK Award.

Activities & Research

1. Create a Jones Family Tree, with images of each family member. Place Grandpa and Grandma Jones at the top, and branch out from there. (Make a list of all the family members before you begin.) Make your family tree look like an authentic Jones Family document. Think about the materials and technology available in the 1940s. Photographs, for example, were printed in black and white. People didn't have computers, either, so they used typewriters, pens, and pencils instead.

2. Study sharecropping and tenant farming. Visit the American Memory page of the Library of Congress at http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/ to learn more. In the search bar, type sharecropping + North Carolina. Look at the photographs. Describe what you see. How do the images compare to the picture created by Shelia Moses? Do they look like what you imagined? Why or why not? Select and print five to ten images that remind you of scenes and characters from The Legend of Buddy Bush. Organize the images in a photo album and label them with passages from the book.

3. Research the Great Migration. This mass movement of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North is perhaps one of greatest population shifts in our nation's history. Why did so many blacks leave the rural South to start a new life in the North? What forces (economic, social, political, agricultural, etc.) pushed African Americans out of the South and into northern cities like New York, Chicago, and Detroit? Visit In Motion: The African American Migration Experience at www.inmotionaame.org/home.cfm and click on The Second Migration (1940-1970) to learn more.

4. Examine Jim Crow laws. Once widespread, these laws limited the rights of African American citizens. Visit www.jimcrowhistory.org/home.htm to learn more. Find examples of Jim Crow laws from North Carolina and other southern states. Did Jim Crow laws exist where you live? If so, what were they?

5. The Legend of Buddy Bush is a work of fiction that's based on real events. Think about the resources Shelia Moses drew upon to create this story, then write your own fictionalized account of a historic event in African American history. Research primary sources (newspaper articles, letters, photographs, drawings, artifacts, oral histories, etc.) to create a realistic story.

6. Stage a mock trial for Buddy Bush. Base your trial on details drawn from the story and your knowledge of American history. Present both sides of the case. Think about what happened from the perspective of Buddy Bush, and from the perspective of his accuser. What testimony would witnesses, including Pattie Mae, have to offer? What verdict will the jury reach?

7. Once Pattie Mae arrives in Harlem, do you think she will write home? To whom would Pattie Mae write? Would she encourage others to come north? Why or why not? How would she describe Harlem? What is new and exciting to her? What is frightening and strange? Who does she meet? How does she spend her time? What, if anything, does Pattie Mae miss about home?

This reading group guide has been provided by Simon & Schuster for classroom, library, and reading group use. It may be reproduced in its entirety or excerpted for these purposes.

Margaret K. McElderry Books • SimonSaysTEACH.com

Product Details

- Publisher: Margaret K. McElderry Books (July 16, 2019)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9781534451452

- Ages: 12 - 99

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"The Legend of Buddy Bush is wonderfully engaging."

– Morgan Freeman, actor director, producer

"Moses captures the hard emotions of one memorable summer that resonates with family love, humor, unbridled prejudice, and loss."

– Angela Johnson, Coretta Scott King Award and Printz Award-winning author of The First Part Last and Heaven

"No one has written a story like this since Mark Twain's Tom Sawyer!"

– Dick Gregory, activist, comedian, actor

"The Legend of Buddy Bush is a must read. I could smell the dirt as I read this wonderful novel."

– Sheila Frazier, Black Entertainment Television

"An important story and...a labor of love."

– Kirkus Reviews

"Shelia Moses, a poet and producer, as well as co-author of Dick Gregory's, A Callus on My Soul, gives the character of Pattie Mae a singular warmth and humor."

– BookPage

Awards and Honors

- National Book Award Finalist

- NYPL 100 Titles for Reading and Sharing

- ALA Coretta Scott King Author Honor Book

- PSLA Fiction List

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Legend of Buddy Bush Trade Paperback 9781534451452

- Author Photo (jpg): Shelia P. Moses Photo Credit:(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit