Get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

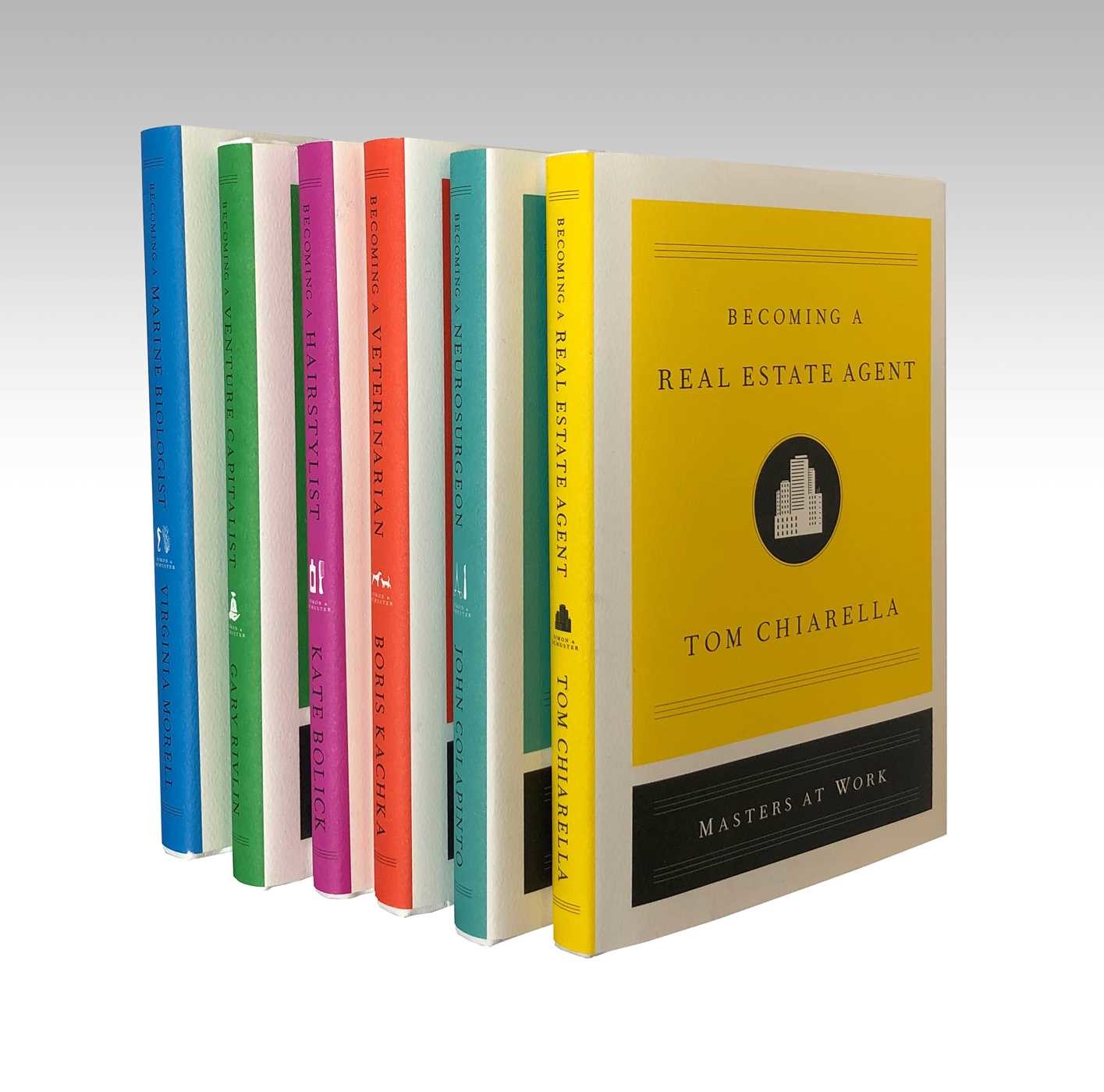

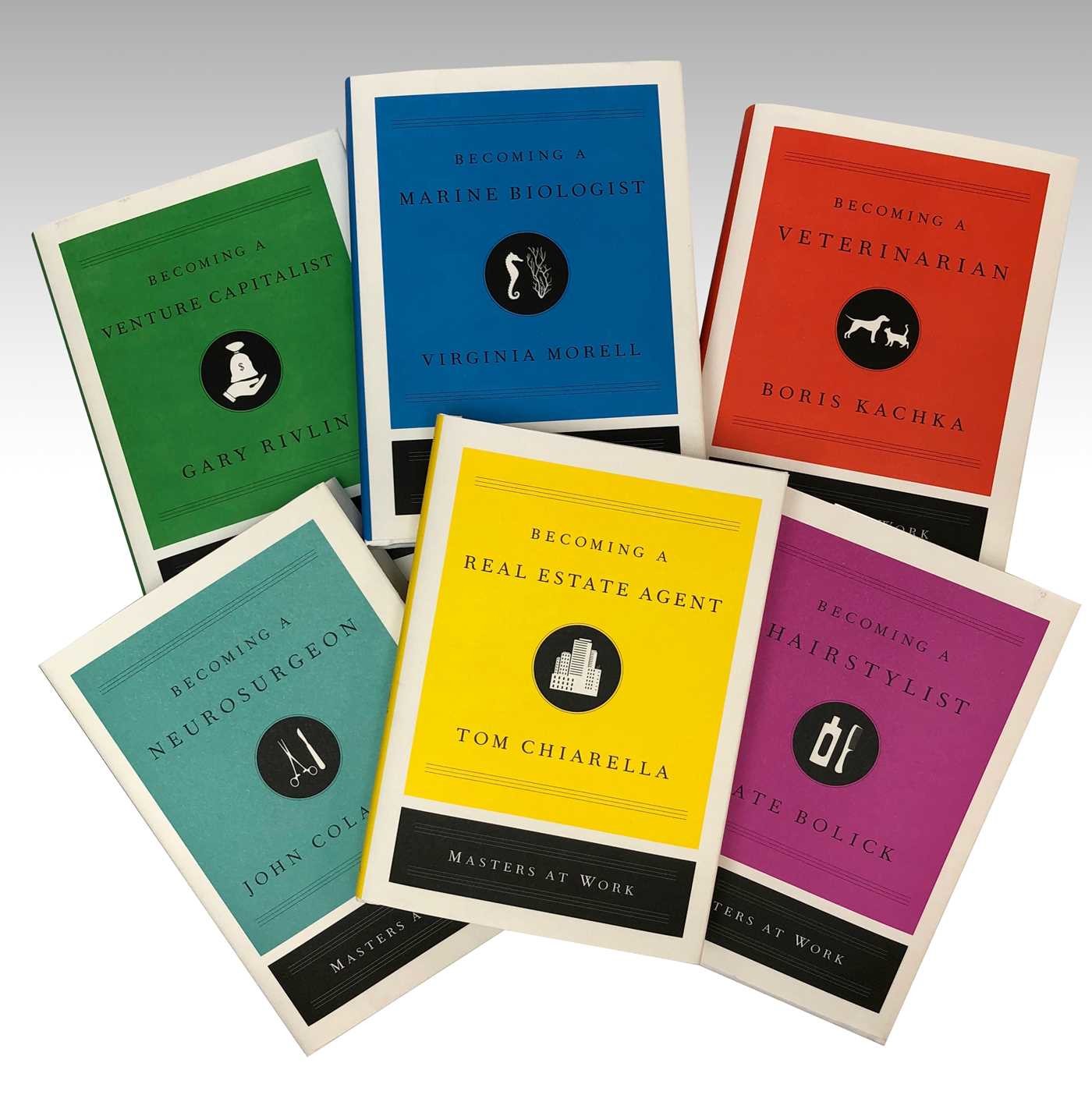

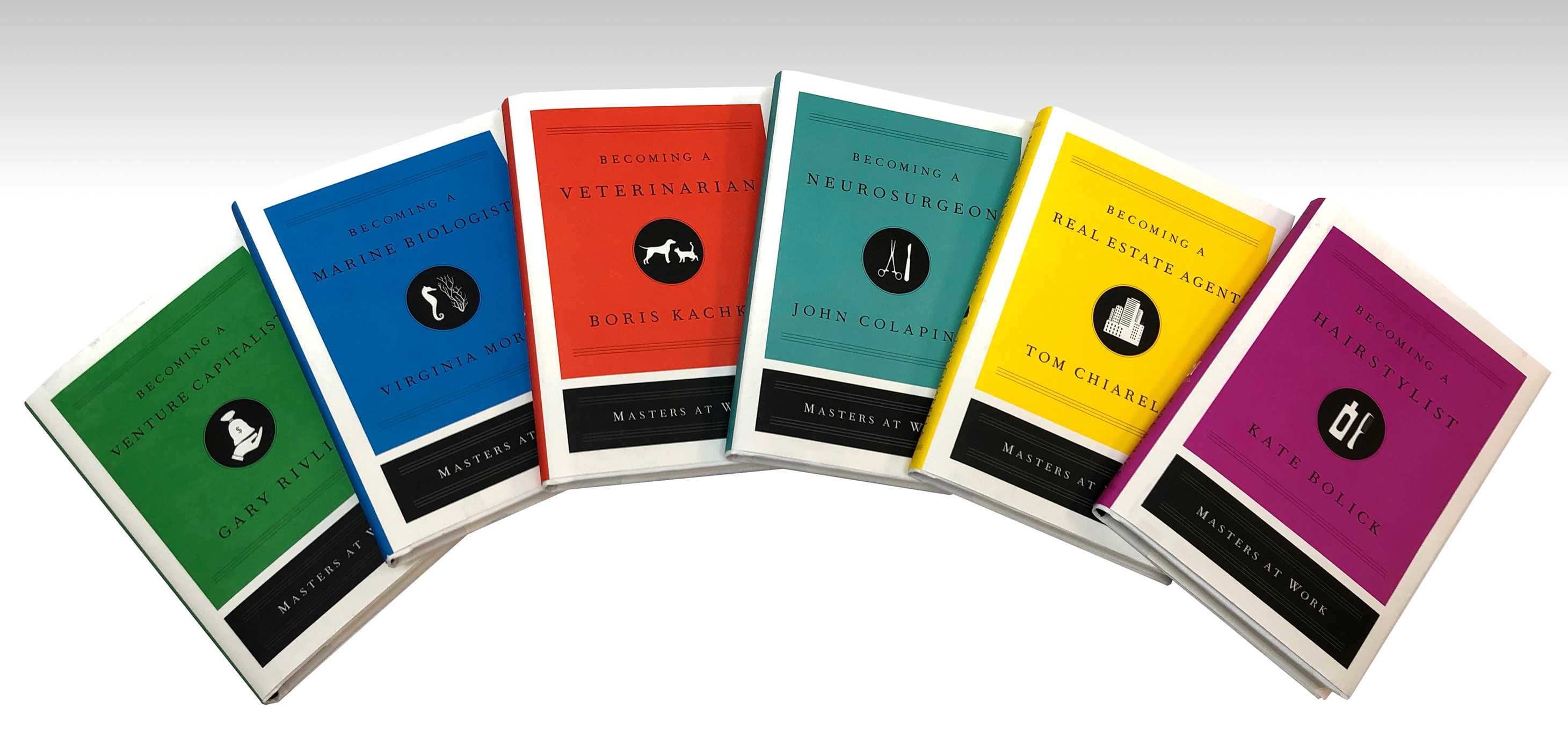

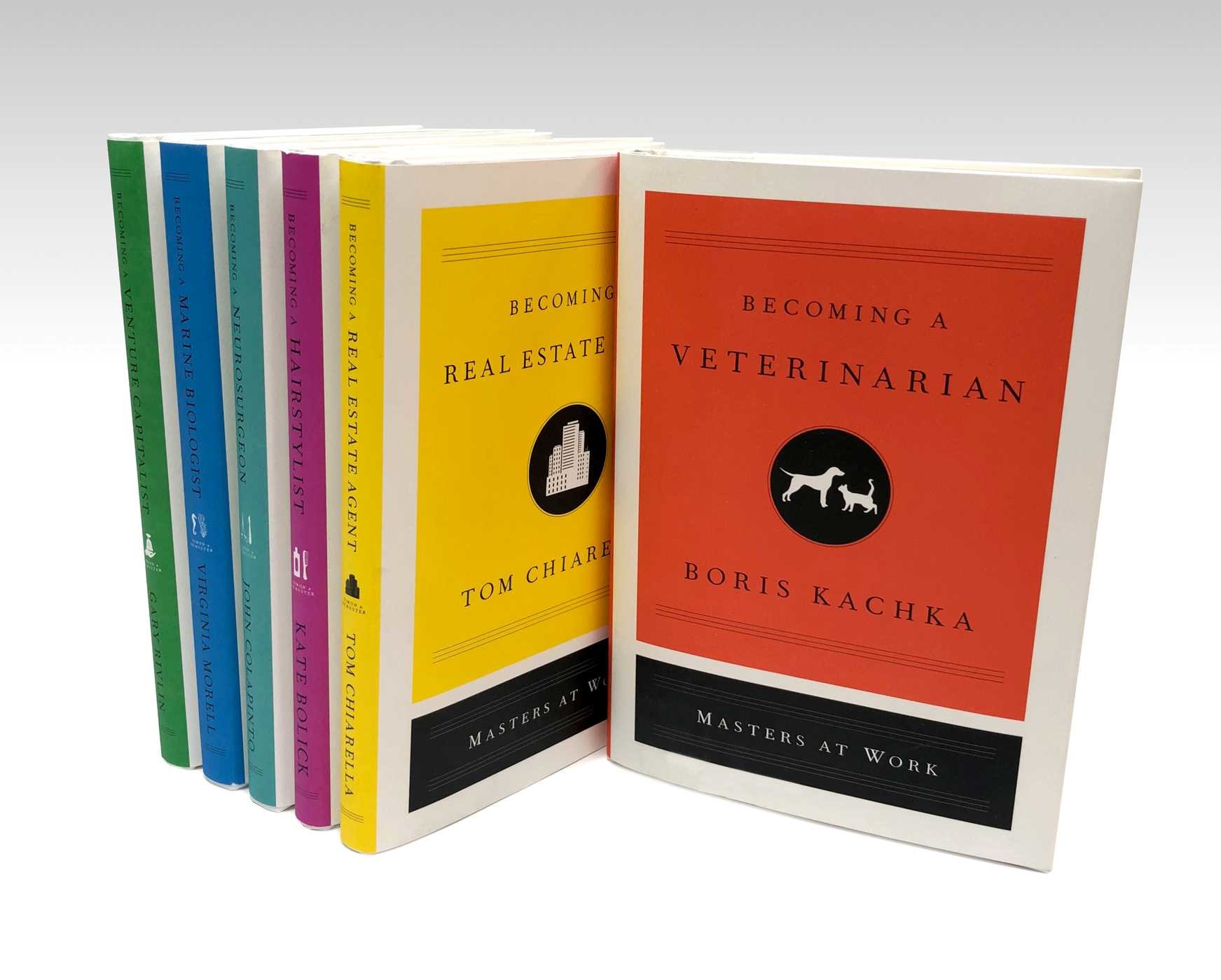

Choosing what to do with your life begins with imagining yourself in a career. Using stories of real practitioners in the field, the Masters at Work series offers the opportunity to see through the eyes of someone who has mastered a profession and learn what the risks and rewards of a job really are.

According to a LinkedIn survey that polled 8,000 professionals, the second most popular childhood dream job for respondents was a veterinarian. It’s a career that appeals to many, due to its involvement with animals and association with helping and doing good. Still, much of the day-to-day elements of the job are not known by the wider public. This series, and individual guide, provides valuable and relevant information about what daily life for a professional veterinarian is like, and will be a vital resource for anyone interested in pursuing the path.

Is there such a thing as a typical veterinarian? Journalist and author Boris Kachka sets out on a journey, determined to discover how to turn a childhood dream into a real career. Becoming a Veterinarian is a behind-the-scenes, honest, and inspiring look at the day-to-day life of a veterinarian through the eyes of four people who have made this career their life’s work. There’s Michael, who thought he would be an architect, but instead works with urban pets at the ASPCA in New York; Elisha, who studied dance before she began treating cows, cats, and horses; Idina, who was injured in a car accident and was forced to find a second career; and Chick, who was earning a Masters in economics but turned to veterinarian science after he began working nights at an animal hospital. With each, Kachka dives into every element of the job: science, surgery, financials, finding a program, and everything in between.

According to a LinkedIn survey that polled 8,000 professionals, the second most popular childhood dream job for respondents was a veterinarian. It’s a career that appeals to many, due to its involvement with animals and association with helping and doing good. Still, much of the day-to-day elements of the job are not known by the wider public. This series, and individual guide, provides valuable and relevant information about what daily life for a professional veterinarian is like, and will be a vital resource for anyone interested in pursuing the path.

Is there such a thing as a typical veterinarian? Journalist and author Boris Kachka sets out on a journey, determined to discover how to turn a childhood dream into a real career. Becoming a Veterinarian is a behind-the-scenes, honest, and inspiring look at the day-to-day life of a veterinarian through the eyes of four people who have made this career their life’s work. There’s Michael, who thought he would be an architect, but instead works with urban pets at the ASPCA in New York; Elisha, who studied dance before she began treating cows, cats, and horses; Idina, who was injured in a car accident and was forced to find a second career; and Chick, who was earning a Masters in economics but turned to veterinarian science after he began working nights at an animal hospital. With each, Kachka dives into every element of the job: science, surgery, financials, finding a program, and everything in between.

Excerpt

Becoming a Veterinarian INTRODUCTION

Elisha Frye was fresh out of Cornell veterinary school, a week into her job at a remote mixed-animal practice in rural Western New York, when her supervisor decided it was time for the rookie to get her hands dirty. Well into their overnight shift, a Mennonite farmer brought in a very pregnant and stoic seven-year-old golden retriever, an over-the-hill breeding dog whose litter wouldn’t come out. A C-section was a fairly routine procedure, but not for Frye, who’d never performed one before, and not for the dog, Sandy, whose condition was worse than it looked.

Frye made a short incision into the dog’s belly, and the first thing she saw was a puppy. The shocked young vet assumed she’d made the possibly fatal mistake of slitting the dog’s uterus. But she quickly concluded the uterus must have ruptured on its own. Three other puppies were floating around in the abdomen, putting Sandy in grave danger of infection. Momentarily panicked, Frye started pulling on what she thought was a uterine horn—a tube ending in an ovary—but turned out to be the colon. “Extend your incision,” her superior advised in a calm tone. “Get the anatomy straight.” Frye found the ruptured horn, pulled out more puppies—eight in total—and spayed the poor overtaxed mother.

It was close to midnight by the time Sandy woke up from anesthesia. Leaving her in her cage overnight, Frye went home wondering if her first surgical patient would be alive in the morning. She hadn’t had time to run the usual preoperative tests, and between blood loss and the risk of infection, there was no way of predicting whether she’d recover. Frye felt she was abandoning Sandy, but she had no choice. The following morning she rushed back and found Sandy energetically wagging her tail, just as she had when she’d first come in. “She recovered like a champ,” says Frye, giving the retriever all the credit for her own quick, lifesaving work.

Eight years after the surgery, I visited the lakeside cabin Frye shares with her husband, Chris, a vet she met at Cornell; their baby daughter, Seneca; a one-eyed cat named Mr. Winks; and a surprisingly agile fifteen-year-old golden retriever—four years past the breed’s average lifespan—who greeted me at the door with that same energetic wag of her tail.

The Fryes adopted Sandy two weeks after her surgery. At the urging of her boss and with Chris’s wary consent (“as long as she’s potty-trained,” which Sandy was, more or less), Elisha paid the Mennonite farmer $30 to take the ex-breeding dog off his hands. Both Fryes knew there was still plenty of work to do—half a lifetime of care. Dogs spayed late in life are at very high risk of mammary cancer, so Elisha removed and biopsied two nipples, which tested negative. In the ensuing years it was Chris’s particular set of skills that gave Sandy her second life. In 2016, Chris finished Cornell’s first residency in animal sports medicine and rehab, which focuses partly on geriatric fitness. The leading vet school’s brand-new department is as specialized as Elisha’s practice is general; Chris is laser focused on dogs’ muscles and nervous systems, while Elisha toggles between cow pregnancy checks, cat emergencies, goat tumors, and the occasional ailing snake.

Showing me around her current workplace, a ten-doctor mixed-animal practice in Cortland, New York, Elisha shows off a new X-ray machine and, suspended high above, the backlit film of a healthy dog femur. It’s Sandy’s hindquarters, and Frye likes to place it side-by-side with the X-rays of arthritic dogs to show owners the effects of a condition that Sandy has somehow evaded. Having eaten well and exercised her whole life, often tagging along on the Fryes’ hikes and snowshoe outings and horseback rides, Sandy has defied all expectations for her age and breed. “It’s crazy that she’s alive, considering everything,” says Frye—never mind fully mobile (if quite deaf). “She’s just this kind of miracle dog.”

The modern doctrine of “work-life balance” dictates that you shouldn’t take your work home with you. But if you want to know what sustains veterinarians through the profession’s downsides—years of training, high debt, relatively low pay, frequent euthanasia—just look at the work they bring home.

Dr. Njeri Cruse, a dreadlocked, Brooklyn-born vet-for-hire who spends most days spaying and neutering pets for the ASPCA, lives with five cats, a mouse, and a ball python, all rescued from illness or neglect. Inbal Lavotshkin, the medical director of a New York–area emergency hospital, owns one dog abandoned by a family after it was hit by a car and another who was dying of heart failure—before Lavotshkin decided to pamper him for one last weekend and then, unwilling to let him go, wrangled him a pacemaker that saved his life.

Veterinarians are as varied as the animals they rescue (and sometimes adopt). They treat an astonishing array of creatures and biological systems, and just as there’s no “typical” animal, there is no typical animal doctor. Maybe there was in the early 1940s, when the country vet James Alfred Wight (pen name James Herriot, author of All Creatures Great and Small) birthed his first calf. And even today, you can make some generalizations about a profession that, for all its range, requires a degree from one of only thirty American graduate schools and another couple dozen foreign institutions.

Our fictional “typical” veterinarian is, increasingly, female. She graduates with the same debt as a human doctor, well into the six figures and sometimes in excess of $300,000, but a much lower starting salary—a median of $70,000. She grew up around animals, whether on a family dairy or in a city teeming with strays of many species. In elementary school, college, or even well into another career, she became driven, possibly obsessed, with doing the very hard work it takes to earn a DVM or a VMD.

She may have been naturally introverted, favoring the innocence of animals to the social needs of humans, only to realize that it’s impossible to be a good vet without liking people. She’s euthanized countless animals in front of their owners, 80 percent of whom consider them family members, after coaching those owners through a level of cost-benefit analysis human patients rarely face. She is probably more susceptible to burnout and depression than most human doctors—but also open to the satisfaction of having heroically spoken up for creatures who can’t describe their pain, and who ask for nothing in return for their companionship or their milk or the biodiversity that enriches our planet.

But no, there is really no typical veterinarian among the more than 100,000 who practice in the United States today, and nothing like a typical veterinary career. Michael Lund grew up in a North Dakota town of 1,300, thinking he might be a rancher or an architect before winding up at the ASPCA in New York, ministering to the pets of the urban poor. Elisha Frye is the daughter of a mixed-animal vet; she studied dance in Manhattan before following in her father’s footsteps. M. Idina O’Brien was a world-class clarinetist until a car accident forced her into a second career—as an emergency-room veterinary surgeon. And Chick Weisse was earning his master’s degree in economics when he took a night job in an animal hospital; a decade later he began inventing surgeries that changed the course of animal medicine.

Just as important as the idea that a vet can come from anywhere is the notion that one can go anywhere. The field is more complicated, in mostly good ways, than it ever was. It’s harder to afford than it was even ten years ago, and it takes more skill and grit and flexibility, but it’s also advancing further into procedures once reserved for humans; more responsive to pets and people in need; more humane to both animals and the overworked doctors who treat them; and more sensitive to the interconnectedness of all species. It’s never been harder to be a vet, and never more exciting.

Elisha Frye was fresh out of Cornell veterinary school, a week into her job at a remote mixed-animal practice in rural Western New York, when her supervisor decided it was time for the rookie to get her hands dirty. Well into their overnight shift, a Mennonite farmer brought in a very pregnant and stoic seven-year-old golden retriever, an over-the-hill breeding dog whose litter wouldn’t come out. A C-section was a fairly routine procedure, but not for Frye, who’d never performed one before, and not for the dog, Sandy, whose condition was worse than it looked.

Frye made a short incision into the dog’s belly, and the first thing she saw was a puppy. The shocked young vet assumed she’d made the possibly fatal mistake of slitting the dog’s uterus. But she quickly concluded the uterus must have ruptured on its own. Three other puppies were floating around in the abdomen, putting Sandy in grave danger of infection. Momentarily panicked, Frye started pulling on what she thought was a uterine horn—a tube ending in an ovary—but turned out to be the colon. “Extend your incision,” her superior advised in a calm tone. “Get the anatomy straight.” Frye found the ruptured horn, pulled out more puppies—eight in total—and spayed the poor overtaxed mother.

It was close to midnight by the time Sandy woke up from anesthesia. Leaving her in her cage overnight, Frye went home wondering if her first surgical patient would be alive in the morning. She hadn’t had time to run the usual preoperative tests, and between blood loss and the risk of infection, there was no way of predicting whether she’d recover. Frye felt she was abandoning Sandy, but she had no choice. The following morning she rushed back and found Sandy energetically wagging her tail, just as she had when she’d first come in. “She recovered like a champ,” says Frye, giving the retriever all the credit for her own quick, lifesaving work.

Eight years after the surgery, I visited the lakeside cabin Frye shares with her husband, Chris, a vet she met at Cornell; their baby daughter, Seneca; a one-eyed cat named Mr. Winks; and a surprisingly agile fifteen-year-old golden retriever—four years past the breed’s average lifespan—who greeted me at the door with that same energetic wag of her tail.

The Fryes adopted Sandy two weeks after her surgery. At the urging of her boss and with Chris’s wary consent (“as long as she’s potty-trained,” which Sandy was, more or less), Elisha paid the Mennonite farmer $30 to take the ex-breeding dog off his hands. Both Fryes knew there was still plenty of work to do—half a lifetime of care. Dogs spayed late in life are at very high risk of mammary cancer, so Elisha removed and biopsied two nipples, which tested negative. In the ensuing years it was Chris’s particular set of skills that gave Sandy her second life. In 2016, Chris finished Cornell’s first residency in animal sports medicine and rehab, which focuses partly on geriatric fitness. The leading vet school’s brand-new department is as specialized as Elisha’s practice is general; Chris is laser focused on dogs’ muscles and nervous systems, while Elisha toggles between cow pregnancy checks, cat emergencies, goat tumors, and the occasional ailing snake.

Showing me around her current workplace, a ten-doctor mixed-animal practice in Cortland, New York, Elisha shows off a new X-ray machine and, suspended high above, the backlit film of a healthy dog femur. It’s Sandy’s hindquarters, and Frye likes to place it side-by-side with the X-rays of arthritic dogs to show owners the effects of a condition that Sandy has somehow evaded. Having eaten well and exercised her whole life, often tagging along on the Fryes’ hikes and snowshoe outings and horseback rides, Sandy has defied all expectations for her age and breed. “It’s crazy that she’s alive, considering everything,” says Frye—never mind fully mobile (if quite deaf). “She’s just this kind of miracle dog.”

The modern doctrine of “work-life balance” dictates that you shouldn’t take your work home with you. But if you want to know what sustains veterinarians through the profession’s downsides—years of training, high debt, relatively low pay, frequent euthanasia—just look at the work they bring home.

Dr. Njeri Cruse, a dreadlocked, Brooklyn-born vet-for-hire who spends most days spaying and neutering pets for the ASPCA, lives with five cats, a mouse, and a ball python, all rescued from illness or neglect. Inbal Lavotshkin, the medical director of a New York–area emergency hospital, owns one dog abandoned by a family after it was hit by a car and another who was dying of heart failure—before Lavotshkin decided to pamper him for one last weekend and then, unwilling to let him go, wrangled him a pacemaker that saved his life.

Veterinarians are as varied as the animals they rescue (and sometimes adopt). They treat an astonishing array of creatures and biological systems, and just as there’s no “typical” animal, there is no typical animal doctor. Maybe there was in the early 1940s, when the country vet James Alfred Wight (pen name James Herriot, author of All Creatures Great and Small) birthed his first calf. And even today, you can make some generalizations about a profession that, for all its range, requires a degree from one of only thirty American graduate schools and another couple dozen foreign institutions.

Our fictional “typical” veterinarian is, increasingly, female. She graduates with the same debt as a human doctor, well into the six figures and sometimes in excess of $300,000, but a much lower starting salary—a median of $70,000. She grew up around animals, whether on a family dairy or in a city teeming with strays of many species. In elementary school, college, or even well into another career, she became driven, possibly obsessed, with doing the very hard work it takes to earn a DVM or a VMD.

She may have been naturally introverted, favoring the innocence of animals to the social needs of humans, only to realize that it’s impossible to be a good vet without liking people. She’s euthanized countless animals in front of their owners, 80 percent of whom consider them family members, after coaching those owners through a level of cost-benefit analysis human patients rarely face. She is probably more susceptible to burnout and depression than most human doctors—but also open to the satisfaction of having heroically spoken up for creatures who can’t describe their pain, and who ask for nothing in return for their companionship or their milk or the biodiversity that enriches our planet.

But no, there is really no typical veterinarian among the more than 100,000 who practice in the United States today, and nothing like a typical veterinary career. Michael Lund grew up in a North Dakota town of 1,300, thinking he might be a rancher or an architect before winding up at the ASPCA in New York, ministering to the pets of the urban poor. Elisha Frye is the daughter of a mixed-animal vet; she studied dance in Manhattan before following in her father’s footsteps. M. Idina O’Brien was a world-class clarinetist until a car accident forced her into a second career—as an emergency-room veterinary surgeon. And Chick Weisse was earning his master’s degree in economics when he took a night job in an animal hospital; a decade later he began inventing surgeries that changed the course of animal medicine.

Just as important as the idea that a vet can come from anywhere is the notion that one can go anywhere. The field is more complicated, in mostly good ways, than it ever was. It’s harder to afford than it was even ten years ago, and it takes more skill and grit and flexibility, but it’s also advancing further into procedures once reserved for humans; more responsive to pets and people in need; more humane to both animals and the overworked doctors who treat them; and more sensitive to the interconnectedness of all species. It’s never been harder to be a vet, and never more exciting.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (April 15, 2019)

- Length: 176 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501159466

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Becoming a Veterinarian Hardcover 9781501159466

- Author Photo (jpg): Boris Kachka Mia Tran(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit